Why do medical specialist consultation fees vary so much?

A new report has revealed substantial variation is the hourly earnings of Australian medical specialists and it isn’t entirely clear what’s justifying it.The ANZ Melbourne Institute’s Health Trends – Specialists report says greater fee transparency is needed as part of the wider policy challenge of ensuring that we are realising full value from the country’s growing health expenditure, says study leader Professor Anthony Scott.

And, he says, insurers and professional member bodies are likely best placed to drive greater transparency in the sector.

“In the current market, patients have little or no information at the point of referral and, therefore, cannot make informed choices regarding the value proposition of different providers and treatments,” says Professor Scott, Program Director Health Economics at the University of Melbourne’s Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research.

“Whether fee transparency will lead to a reduction in fee variation and eradicate some of the very high fees causing understandable public concern, will really depend on how GPs and patients access the information at the time of referral and how specialists themselves react.”

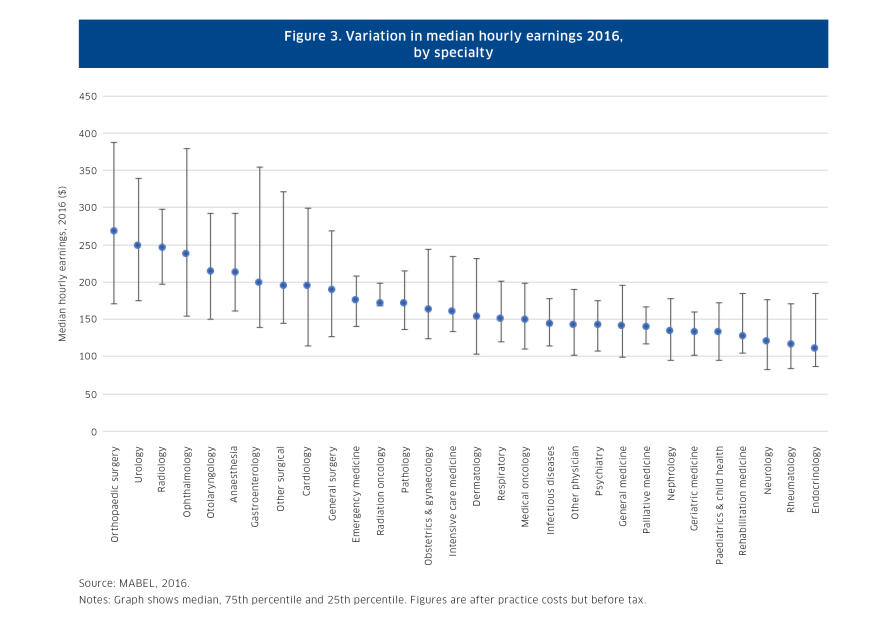

The report cites Professor Scott’s Medicine in Australia: Balancing Employment and Life survey of doctors that found significant within-specialty and between-specialty variation in earnings, particularly between surgical and non-procedural specialty groups.

The highest earning group is orthopaedic surgeons, where median hourly earnings are 2.4 times higher than those of endocrinologists at the lowest end of the scale. But among orthopaedic surgeons themselves, hourly earnings at the top are 2.3 times those at the bottom.

Medicare data also shows significant fee variation within-specialty. For example, in 2016 within neurology there was a 125 per cent difference between consultation fees at the lowest and highest ends of the scale.

But on the positive side, the report found that rising spending in health is being driven by volume, not fees. Average prices per service, including both the government’s Medicare fee and the provider fee, actually fell in real terms by 0.15 per cent in the ten years to 2015-16.

Research suggests some of the fee disparity reflects private practice costs, location, equipment, the time required and the complexity of procedures. But Professor Scott says these cost inputs aren’t the full story.

While a provider’s reputation and expertise could also be expected to drive fees, he says the problem is that customers (both patients and general practitioners) generally lack the information to make these judgements.

“The fact that GPs and patients have little information on quality and costs suggests that other factors are likely playing a role,” says Professor Scott.

Indeed, he points out that other research has demonstrated that some specialists simply price-discriminate by charging higher fees to higher income earners.

Professor Scott says, in the UK, government-funded surgeons now have their performance listed on the NHS Choices website, including risk adjusted mortality rates; additionally, British GPs are legally required to offer patients a choice of specialists.

But he cautions that simply publishing market information on a website may not work because patients could find the information difficult to interpret.

In addition, he says, publishing mortality rates could simply encourage practitioners to treat more healthy patients. There’s also the risk that providers will look at each other’s fees and increase them to the highest charge. He says that research in the US suggests better published information hasn’t led to patients making better choices.

“What we need is more targeted interventions on providers, like health insurers, professional bodies and perhaps government, directly asking providers to justify their prices where there is wide variation,” says Professor Scott. “Doctors are very competitive and would respond to this sort of pressure.”

The report says that a key challenge is to reduce the amount of low-value or unnecessary care – it notes that the OECD estimates that about one-fifth of world health spending makes minimal or no contribution to good health outcomes.

“We need to address low-value care, over-treatment and over-diagnosis at the same time as we call for transparency and accountability from Australia’s specialists,” says Professor Scott.

The report also highlights that the growth in the number of medical specialist is outstripping growth in the number of general practitioners. But it warns that limited access to expensive training places in hospitals and other settings is creating “bottlenecks” meaning that would-be specialists are facing increased competition and delays for training.

“Some of these doctors could end up under-employed and working part-time when they would prefer work full-time; or in jobs that don’t fully utilise their training; or leave clinical practice altogether,” the report says.

While an increasing in the number of specialists could normally be expected to drive down fees, the report cautions that it isn’t clear that would happen.

“The increase in the number of specialists has been occurring for sometime and there is no sign that the sector overall is losing steam in terms of earnings and revenue growth,” says the report.

“Though the need for healthcare services sometimes seems limitless, governments, insurers and patients need to make choices about how to best use the ten per cent of gross domestic product currently spent on healthcare.”

This article was written by Niamh Cremins and Andrew Trounson of the University of Melbourne and published by Pursuit.

Andrew Trounson is a senior journalist for the University of Melbourne’s Pursuit magazine. He was previously an education correspondent for The Australian.