Why digital government isn’t working in the developing world

The digital transformation of society has brought many immediate benefits: it’s created new jobs and services, boosted efficiency and promoted innovation. But when it comes to improving the way we govern, the story is not that simple.

It seems reasonable to imagine introducing digital information and communication technologies into public sector organisations – known as “digital government” or “e-government” – would have a beneficial impact on the way public services are delivered. For instance, by enabling people to claim rebates for medical bills via a government website.

When implemented well, e-government can reduce the cost of delivering government and public services, and ensure better contact with citizens – especially in remote or less densely populated areas. It can also contribute to greater transparency and accountability in public decisions, stimulate the emergence of local e-cultures, and strengthen democracy.

But implementing e-government is difficult and uptake among citizens can be slow. While Denmark – the number one ranked country in online service delivery in 2018 – sees 89% of its citizens using e-services, many other countries are struggling. In Egypt, for example, uptake of e-services is just 2%.

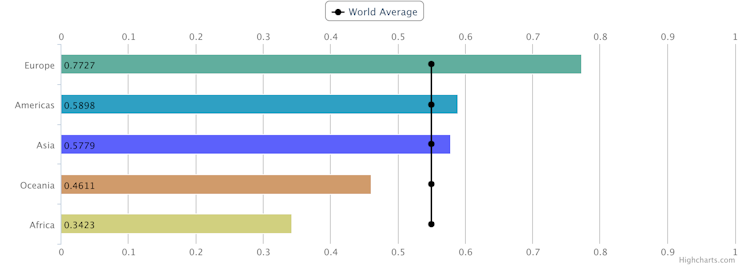

United Nations E-Government Survey 2018

I argue the implementation of digital government is a intractable problem for developing countries. But there are small steps we can take right now to make the issues more manageable.

Few digital government projects succeed

The nature of government is complex and deeply rooted in the interactions among social, political, economic, organisational and global systems. At the same time, technology is itself a source of complexity – its impacts, benefits and limitations are not yet widely understood by stakeholders.

Given this complexity, it’s not uncommon for many digital government projects to fail, and not just in the developing world. In fact, 30% of projects are total failures. Another 50-60% are partial failures, due to budget overruns and missed timing targets. Fewer than 20% are considered a success.

In 2016, government spending on technology worldwide was around US$430 billion, with a forecast of US$476 billion by 2020. Failure rates for these kinds of projects are therefore a major concern.

What’s gone wrong in developing countries?

A major factor contributing to the failure of most digital government efforts in developing countries has been the “project management” approach. For too long, government and donors saw the introduction of digital services as a stand-alone “technical engineering” problem, separate from government policy and internal government processes.

But while digital government has important technical aspects, it’s primarily a social and political phenomenon driven by human behaviour – and it’s specific to the local political and the country context.

Change therefore depends mainly upon “culture change” – a long and difficult process that requires public servants to engage with new technologies. They must also change the way they regard their jobs, their mission, their activities and their interaction with citizens.

In developing countries, demand for e-services is lacking, both inside and outside the government. External demand from citizens is often silenced by popular cynicism about the public sector, and by inadequate channels for communicating demand. As a result, public sector leaders feel too little pressure from citizens for change.

For example, Vietnam’s attempt in 2004 to introduce an Education Management Information System (EMIS) to track school attendance, among other things, was cancelled due to lack of buy-in from political leaders and senior officials.

Designing and managing a digital government program also requires a high level of administrative capacity. But developing countries most in need of digital government are also the ones with the least capacity to manage the process thus creating a risk of “administrative overload”.

How can we start to solve this problem?

Approaches to digital government in developing countries should emphasise the following elements.

Local leadership and ownership

In developing countries, most donor driven e-government projects attempt to transplant what was successful elsewhere, without adapting to the local culture, and without adequate support from those who might benefit from the service.

Of the roughly 530 information technology projects funded by the World Bank from 1995 to 2015, 27% were evaluated as moderately unsatisfactory or worse.

The swiftest solution for change is to ensure projects have buy-in from locals – both governments and citizens alike.

Public sector reform

Government policy, reflected in legislation, regulations and social programs, must be reformulated to adapt to new digital tools.

The success of digital government in Nordic countries results from extensive public sector reforms. In the United States, investments in information technology by police departments, which lowered crime rates, were powered by significant organisational changes.

In developing countries, little progress has been made in the last two decades in reforming the public sector.

Accept that change will be slow

Perhaps the most easily overlooked lesson about digital government is that it takes a long time to achieve the fundamental digitisation of a public sector. Many developing countries are attempting to achieve in the space of a few decades what took centuries in what is now the developed world. The Canadian International Development Agency found:

In Great Britain, for example, it was only in 1854 that a series of reforms

was launched aimed at constructing a merit-based public service shaped by rule of law. It took a further 30 years to eliminate patronage as the modus operandi of public sector staffing.

Looking to the future

Effective strategies for addressing the problem of e-government in developing countries should combine technical infrastructure with social, organisational and policy change.

The best way forward is to acknowledge the complexities inherent in digital government and to break them into more manageable components. At the same time, we must engage citizens and leaders alike to define social and economic values.

Local leaders in developing countries, and their donor partners, require a long-term perspective. Fundamental digital government reform demands sustained effort, commitment and leadership over many generations. Taking the long view is therefore an essential part of a global socio-economic plan.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Rania Fakhoury is a ICT Manager Executive with over than 20+ years of achievement in coordinating and managing multiple projects for internet service provider, production industry and government entities. She currently teaches at Université Libanaise.