What’s next for the National Cabinet?

As the COVID-19 crisis began to escalate in Australia, a new institution, the National Cabinet, emerged.

Its members are the Prime Minister and the Premiers and Chief Ministers of the eight Australian States and Territories.

The National Cabinet consists of the Prime Minister and the Premiers and Chief Ministers of the eight Australian States and Territories.

The National Cabinet deserves considerable credit for the (so far) very effective response to the pandemic in Australia, in which the rate of infections was flattened over a relatively short period of time, while governments rapidly developed testing and tracing, as well as hospital and medical services to cope with increasing demand.

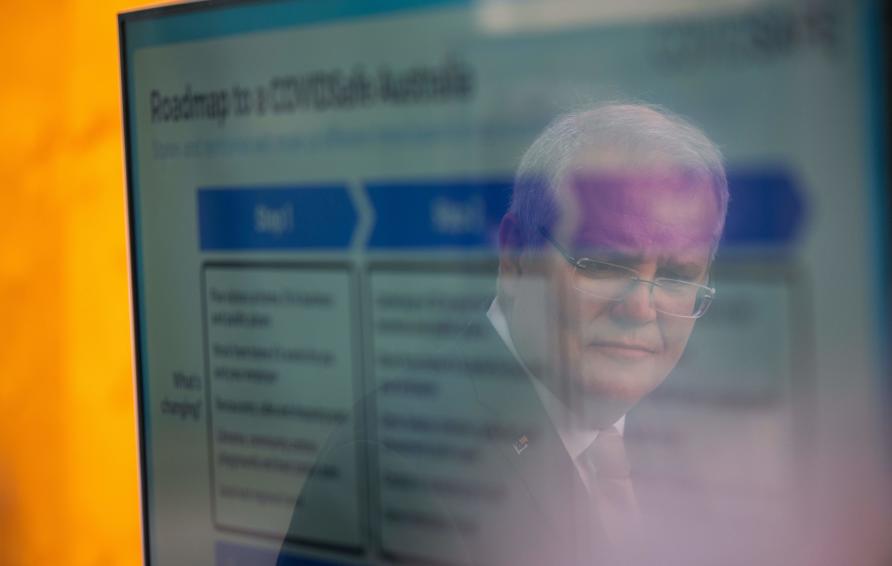

In late May, the Prime Minister announced that the body would be continued, replacing the existing intergovernmental architecture under the Council of Australian Governments (COAG).

An outline for the structure of the new arrangements has been released, presenting the National Cabinet and the Council on Federal Financial Relations (CFFR) as the two principal components of a National Federation Reform Council, supported by two task forces, seven National Cabinet Reform Committees and a series of intergovernmental expert advisory groups.

The chart identifies a further 28 ministerial forums or regulatory councils that need to be ‘consolidated and reset’.

But the success of this initiative depends on how it works in practice, once the immediate health crisis passes.

Lessons for the future can be drawn from considering why the National Cabinet seems to have worked better than other intergovernmental processes. It is worth thinking also about how pressures to return to the past can be resisted, if this new approach is to succeed.

COAG was established in 1992 and is associated with the success of the microeconomic reforms that centred around competition policy.

Scott Morrison has announced that the National Cabinet will continue.

By 2020, however, the COAG system was a lumbering network of ministerial councils and forums with COAG itself at the top. It was heavily bureaucratised, with ministerial discussions prepared by (sometimes layers of) intergovernmental meetings of officials.

The frequency and timing of meetings, and the structure of COAG councils, varied with the preferences of the incumbent Commonwealth government.

Most significantly, COAG was a top-down process, driven by Commonwealth priorities and Commonwealth perceptions of issues and desired outcomes. Formal State and Territory compliance ultimately could be procured through the Commonwealth’s financial dominance, used either as a carrot or a stick.

The secretariats for most councils were located in the Commonwealth public service, answerable to Commonwealth Ministers.

Post-meeting accountability took the form of a bland communique. Not surprisingly, in these circumstances, State and Territory governments had little ownership of outcomes.

Intergovernmental activity managed to be both pervasive and underwhelming.

While there was no announcement of the working rules for National Cabinet at the outset, some features were clear enough.

The National Cabinet has provided a forum for agreement between government leaders on collective action.

The National Cabinet was a response to an urgent public health crisis that could not be effectively met without drawing on the powers, knowledge and capacities of both the Commonwealth and the States.

It provided a forum for agreement between government leaders on collective action, ranging from procurement of medical supplies to co-ordinating consistent policy positions.

It also accepted the need for diversity, as governments responded to local conditions or preferences, sometimes in innovative ways, taking public responsibility for their own positions.

It had the additional advantage of bringing together governments from different sides of the political divide, defusing tendencies to engage in politics for politics’ sake. It met as often as was needed.

The National Cabinet did not work perfectly.

There were disagreements between the Commonwealth and States over face-to-face schooling and between some States over the reopening of internal borders. There was buck-passing between the Commonwealth and New South Wales over responsibility for passengers from the Ruby Princess.

What was impressive, however, is that such problems were overcome and the process moved on. In the end, they did not detract from the National Cabinet as an effective, genuinely intergovernmental process, responding to an urgent public need in ways the public could trust.

As the immediate crisis dies down, there will be pressures to revert to old-style intergovernmental relations, dominated by the command and control techniques that the National Cabinet process has discredited by example.

The National Cabinet incorporated diversity as State governments responded to local conditions or preferences.

The current government leaders, who have experienced the workings of the National Cabinet, can be expected to maintain its ethos for a while. Fleshing out the embryo structure that was released on 29 May will be a critical next step.

In the end, however, the continuation of effective intergovernmental relations between Australian governments in the exercise of shared or complementary powers requires the understanding, endorsement and support of Parliaments, the media and the public at large.

To achieve this, there is a way to go.

For too long, intergovernmental arrangements have been treated as the business of executive government, rather than as a critical cog in the wheel of Australian federal democracy. Not enough attention has been paid to accommodating intergovernmental arrangements to the cabinet and parliamentary processes at each level of government.

The first phase of the operations of the National Cabinet has helped to arouse public interest and understanding, but this must be encouraged if it is to be sustained.

The terminology of ‘National Cabinet’ is a hindrance in this regard.

In Australian parlance, ‘national’ has come to signify a genuinely collaborative process, owned by all participating jurisdictions, rather than the preserve of one jurisdiction alone.

Governments rapidly organised hospital and medical services to cope with increasing demand.

On no view, however, is this body a ‘cabinet’ as the term is used elsewhere in parliamentary government. A Cabinet is a group of Ministers drawn from and collectively accountable to the same Parliament.

What presently is called the ‘National Cabinet’ is a group of chief ministers, heading different cabinets, through which they are individually and collectively accountable to different Parliaments and different configurations of the people for the exercise of different powers.

That, indeed, is the whole point.

Use of the terminology of cabinet is misleading. If it were to cause the superimposition of ideas about decision-making drawn from the more familiar kind of cabinet, the chance to make this important initiative work would be lost.

The problem is compounded by the suggestion that, somehow the National Cabinet fits within the Commonwealth cabinet structure. This is a logical impossibility, apparently driven by a desire to keep proceedings confidential.

It may readily be accepted that an intergovernmental ‘National Cabinet’ requires forms of solidarity and some respect for confidentiality. These should be crafted to fit this distinctive need, however, not imported from a conceptually different source.

Professor Cheryl Saunders is a President Emeritus of the International Association of Constitutional Law. Her interests include comparative constitutional law and method, intergovernmental relations and constitutional design and change.