There’s clear water between the parties on housing policy

Labor’s bold stance on housing tax reform and investment makes this one of the likely policy flashpoints in the coming election campaign. How does the Coalition government’s housing record stand up to scrutiny? What would be in prospect in a third Liberal-National term? And exactly what is Labor’s alternative pitch?

The Coalition record

Under the Abbott-Turnbull-Morrison governments we’ve seen a housing market featuring both rampant inflation and damaging volatility. Despite recent falls in some cities, late 2018 prices remained 29% up on 2013 across the country – 42% in Sydney.

While first home buyer numbers grew in 2018, the total remained well below 2007 (pre-GFC) levels. Unless this changes the rate of young adult home ownership is likely to drift still lower.

During this term of government, official action to moderate housing market instability has been left almost entirely to the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, through their influence on the cost and accessibility of housing finance.

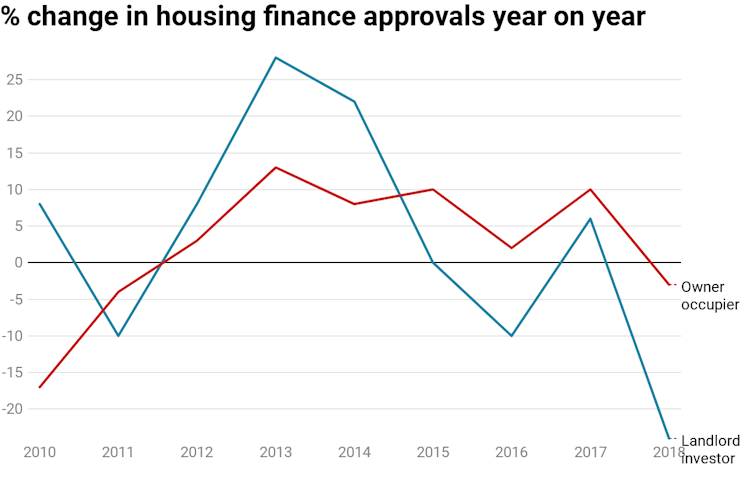

The government has mostly turned a blind eye to more far-reaching reforms that could squarely address Australia’s boom-and-bust housing dynamic. The prime source of recent volatility has been the erratic behaviour of landlord investors, as the chart below shows. They are responsible for around 35% of residential transactions across the country.

Australia’s unusually favourable tax settings on negative gearing and capital gains tax discount compound investors’ speculative instincts. Calls for reform have been growing, from sources as diverse as a Liberal state government minister and the Reserve Bank. And the annual cost to the public purse has been rising – most recently estimated at A$11.7 billion. Despite this, federal Coalition ministers have resisted any paring back of these concessions.

The Labor alternative

The ALP enters this election campaign restating its 2016 policy to restrict current negative gearing to newly built properties and to halve the CGT discount for all newly purchased rental homes.

While sectional interests have echoed government claims of damaging market impacts, mainstream economists view the policy as a necessary structural reform that will slightly moderate house price inflation over the longer term. However, with all existing investments exempt from proposed changes, the budgetary pay-off would be modest at first.

Labor also advocates rebalancing the tax treatment of large-scale institutional investment in rental housing. According to industry proponents, resulting “build to rent” development could help to diversify the housing market and provide a better quality tenancy offer. It would also have the benefit of introducing a counter-cyclical component to residential construction.

Housing stress on the rise

The Coalition government has also presided over intensifying stress at the lower end of the housing market since 2013. Homelessness has been increasing by 2.8% a year. The proportion of low-income tenants facing unaffordable rents rose by four percentage points in the four years to 2015-16.

At least in part, these trends reflect Coalition government disinterest. While slightly moderated under the Turnbull-Morrison administrations, the die was cast with the incoming government’s 2013 decision to abolish the post of housing minister and by the Abbott inclination to re-emphasise a minimalist vision of Federal government responsibilities. The new government was quick to abandon Kevin Rudd’s 2008 commitment to halve homelessness by 2020.

To the credit of the Turnbull-Morrison governments, a project begun in 2016, when Morrison was treasurer, has created a new institution to open up access to cheaper, longer-term finance for community housing providers.

Through its first bond, issued only last month, the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation (NHFIC) has enabled six of these providers to secure debt finance on much-improved terms. This will boost recipient organisations’ financial “headroom”. A worthwhile – but modest and one-time-only – addition to affordable housing stock may result.

Subsidies needed to restore supply

Importantly, though, the cheaper debt finance made available through the NHFIC only narrows – rather than bridges – the gap between the cost of delivering social housing and the rents that low-income Australians can afford.

A major social housing investment program will require a complementary government subsidy. The treasurer’s own advisory working group has unambiguously stated the need for such provision.

Curiously, the government has yet to give any sign it intends to finish what it started here. Without the necessary gap-filling subsidy, there must be a danger that – perhaps after exhausting the potential for refinancing community housing providers – the NHFIC could become a white elephant.

Indeed, the Coalition’s most significant action on affordable rental housing supply was its 2014 cancellation of the Rudd government’s National Rental Affordability Scheme. Mainly targeted at low-income workers, the NRAS generated 38,000 discount-to-market rental units (against an original target of 50,000).

The ALP is now promising to re-establish a large-scale supply program. As well as restricting landlord investor tax concessions to new-build properties, Labor’s 2019 pitch includes a program similar to NRAS with the aim of generating 250,000 new affordable rental homes over a decade. A shorter-term target of 20,000 dwellings during the next term of government would equal the Rudd government’s 2009-12 social housing stimulus, which helped to stave off the GFC.

Supported through subsidy in the form of annual investor incentive payments of $8,500 for 15 years, the program would be mainly targeted at “key workers” and “lower-income families”. Tenants would pay rents of 20-25% below market levels. Beyond this, the program could help more disadvantaged Australians, but only with matching financial assistance or other subsidies from states and territories, which would enable rents to be even lower.

The Coalition’s current offer

Other than its push-back on Labor proposals, the Coalition has – as yet – said little about its election policy on housing. Last week’s budget offered nothing to suggest that, beyond a defence of the policy status quo, housing initiatives are front of mind for the Treasurer or Prime Minister.

The government will maintain the NHFIC, one of its really positive recent moves. The complementary – and overdue – review of social housing regulation will also continue. We can probably expect more City Deals, which may even, as in the recent Hobart announcement, include some provision for affordable housing.

The budget’s infrastructure program, including fast urban rail, might have implications for housing accessibility and affordability. But, if so, these aspects don’t feature prominently in the announcements.

But beyond continuing existing policy directions, nothing much seems likely to be added to the Coalition’s 2019-22 offer on housing. It isn’t proposing any action on the imbalanced tax settings that fuel housing market volatility, let alone any policy to boost affordable housing supply directly. Neither is there any sign of support for the build-to-rent sector, which promises much but appears as yet still-born.

It seems fear of change continues to dominate Coalition thinking on housing. The overriding priority remains to support existing property values, rather than to act on unaffordability – a Boomer protection racket par excellence! Recent ministerial statements offer little indication that a re-elected Coalition government would make a serious effort to fix Australia’s increasingly under-performing housing system.

This article was written by Hal Pawson, Associate Director of Urban Policy and Strategy at the City Futures Research Centre and Bill Randolph, the Director of the same institution. It was published by The Conversation.

Hal Pawson joined UNSW in 2011 as a Professor of Housing Research and Policy at the City Futures Research Centre. His research interests include the governance and management of social housing, private rental markets and urban renewal.