Barneys, the iconic chain of upscale New York department stores established in 1923, has just filed for bankruptcy protection. Another of America’s great department store brands, Chicago’s Sears (dating from 1925), did the same a year ago.

Times are tough for department stores all over. In Britain, Debenhams – whose origins go back to the 18th century – went into administration in April. It has closed about a third of its stores in the past year or so, and will close more in the next, including its only store in Australia.

Meanwhile Australia’s once dominant Myer and David Jones chains are in a “death spirals”, according to retail experts.

The internet is a big part of the problem faced by these once mighty retail empires. Foot traffic has declined as people’s fingers do the browsing and shoppers buy direct from online retailers.

But there’s another reason also, indicative of a social shift just as profound. The rise of the department store symbolised the rise of middle class. Its collapse mirrors the hollowing out of the same.

The shifting centre of gravity

In May the OECD published a major report on the state of the middle class around the world. It defines “middle-income households” as those with incomes between 75% and 200% of median household income.

In emerging economies this is where one-third to half of households fall. In OECD nations it’s an average of 61%. But it was 64% in the mid-1980s, the report says.

Thus the economic “centre of gravity” is tilting away from the middle: “Income growth in the middle has been much weaker than at the top. In the mid-1980s, the combined income of all middle-income households was four times the aggregate income of all upper-income households. Currently, it is less than three.”

The report notes in particular the reduced chances of families with children and young adults having middle incomes: “In contrast to 30 years ago, most single-parent families are today in the lower-income class and young adults are the least likely of all age groups to be in middle-income households.”

Though these percentage changes might seem comparatively small, the trend fits a retail phenomena grandly labelled “the great retail bifurcation”.

What this means is that retailers are succeeding by focusing on either the luxury end of the market or on the bargain-basement end. Retailers in the the middle are falling away.

The discount market

In the US, for example, this bifurcation effect has seen a boom in discount stores such as Dollar General, which sells cheap consumable items. Its revenue in the first quarter of 2019 was US$6.62 billion, up 8.3% on the previous year.

A Dollar General store in Leesport, Pennsylvania.

The company now has more than 15,000 stores in the US. Bucking general retail industry trends, it opened 900 stores in 2018 and plans to open 975 more in 2019. Other discount store chains – Dollar Tree, Family Dollar, Aldi, Five Below, Ross Stores and Ulta – are also expanding.

The luxury market

At the other end of the spectrum are retailers such as French high-fashion luxury goods brand Hermès. This company sells things like $500 t-shirts, $750 beach towels and $1,000 sweaters. Its 2018 profit was up 15% to US$1.6 billion.

A Hermès store in Lisbon, Portugal.

While the proportion of households that are upper-income (earning 200% or more of the median income) has increased only marginally since the 1980s, the incomes of those households has increased more than those on middle incomes. OECD figures show upper-income households now comprise, on average, 10% of households and 18% of spending.

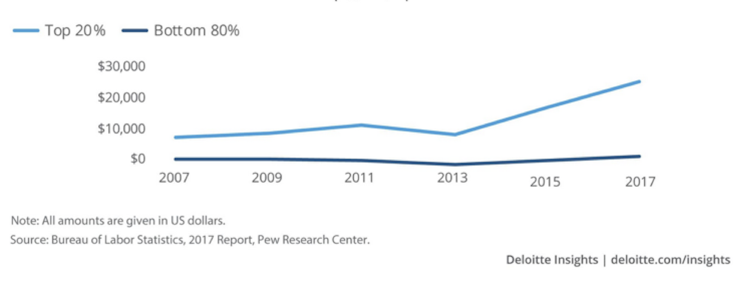

The chart below indicates increases in discretionary spending in the United States over the past decade has occurred only among the top 20% of households by income.

A model on its last legs?

Arguably, the discount and premium retailers having success also happen to be stores, brands and categories more resistant to what’s going on in e-commerce.

For instance, many discount retailers supply the type of goods consumers want quickly. A packet of chips, for example, or toilet paper. The convenience factor means these shops are more immune to digital disruption.

Luxury brands are likely even more immune from online competition. If money is no object, you’re unlikely to spend your nights browsing eBay looking for the cheapest price.

What is indisputable, though, is that the department store model is struggling globally, particularly in the Anglophone world of the United States, Britain and Australia, where there have been significant falls in the upper-middle and middle-income classes.

Groups like Myer in Australia have embraced a strategy of downsizing as an alternative to store closures, but that may be simply delaying the inevitable.

This article was written by Jason Pallant, a Lecturer of Marketing at Swinburne University of Technology, and Sean Sands, an Associate Professor of Marketing at the same institution. It was published by The Conversation.