The moral market

It is fashionable these days to dunk on markets. Show me something bad in the world and I’ll show you someone blaming it on “neoliberalism”.

Our collective failure to tackle climate change – that’s the fault of “neoliberalism”. Poverty, low wages, income inequality, housing affordability, imperfect health care and education systems – the culprit is “neoliberalism”.

Not so long ago – in the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s, the eras of Hawke and Keating in Australia, Clinton in the US and Blair in Britain – markets were seen by those on the centre-left as the best way to create broad prosperity and what is sometimes called “inclusive growth”.

Then a funny thing happened on the way to the 2010s.

A semi-apocalyptic global financial crisis in 2008 turned “market” into a dirty word. A bunch of greedy but clever Wall Street types transformed mortgage-backed securities – a way to bundle up mortgages into bonds leading to lower borrowing costs and greater home ownership – into what famous investor Warren Buffett once called “weapons of financial mass destruction”.

In the wash-up of the financial crisis the good and bad aspects of markets were fused into one derogatory word: neoliberalism.

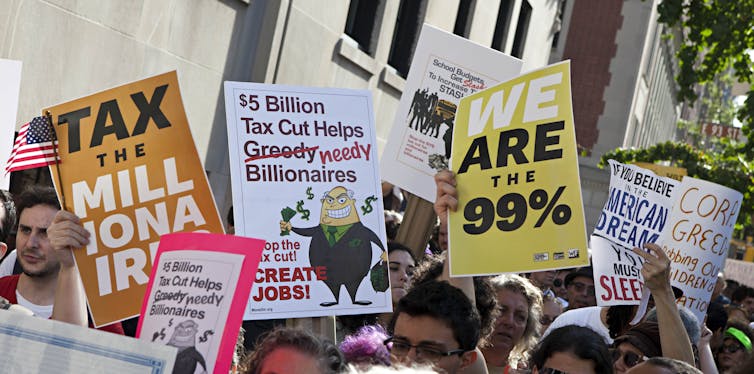

An Occupy Wall Street protest in New York, outside the home of the chief executive of JP Morgan Chase, on October 11 2011.

Belief in the power of markets to lift people out of poverty, empower households, and provide the resources to create a meaningful social safety net has become conflated with the free-market fanaticism associated with Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

This is a big mistake. Those on the left of politics should embrace markets. Not the fanatical laissez-faire views that oppose government and market regulation. But a view of liberalism – in the classical sense, emphasising individual liberty – that harnesses the power of markets for social and economic good.

Towards democratic liberalism

Two of my former colleagues at the University of Chicago, Raghuram Rajan and Luigi Zingales, capture a version of this in their brilliant 2003 book Saving Capitalism from the Capitalists. So too does Joe Stiglitz with his vision of “progressive capitalism”.

My take is articulated in my new book with Rosalind Dixon, From Free to Fair Markets: Liberalism after COVID-19, to be published by Oxford University Press next month, where we argue for “democratic liberalism”.

For us, democratic liberalism takes more seriously commitments to individual dignity and equality, as well as freedom, within the liberal tradition; placing the democratic citizen at the centre of a liberal approach.

It draws heavily on the “capabilities approach” to human welfare of Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum, which acknowledges it’s not enough just to have a “level playing field”. It insists on universal access to dignity, a “generous social minimum” for all. And it insists unregulated markets do not serve those ends.

‘Capitalism is irredeemable’

In particular, so-called “neoclassical” economists have long maintained that monopoly power (in business or politics) and externalities, such as carbon pollution, distort and damage markets.

We need to do more to make markets work better – not abandon markets altogether.

As Buffett said:

“We ought to do better by the people that get left behind by our capitalist system. I don’t think we should kill the capitalist system in the process.”

Contrast this with the US left’s icon du jour, New York congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who in 2019 said capitalism was irredeemable.

Asked what she meant by this last month, she described capitalism as:

“the ability for a very small group of actual capitalists – and that is people who have so much money that their money makes money and they don’t have to work – to control industry. They can control our energy sources. They can control our labour. They can control massive markets that they dictate and can capture governments. And they can essentially have power over the many.”

To be fair, that doesn’t sound so great to me either.

And I get that Ocasio-Cortez is not a fusty scholar but a (very successful) politician and activist. Nuance doesn’t play well in those worlds. But nuance is required when thinking about how society should be arranged.

We’ve been here before

This isn’t society’s first rodeo on these matters.

One of the more consequential debates about liberalism versus socialism – which became known as the socialist calculation debate – began in the 1920s between neoclassical economists Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek and socialist economists Fred Taylor, Oskar Lange and Abraham “Abba” Lerner.

At issue was whether Soviet-style socialism and its central planning could replicate the virtues of free markets without the downsides of inequality.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez on-message at New York City’s high-society event the Met Gala in September 2021. NDZ/STAR MAX/IPx/AP

The clinching argument in this debate came from Hayek, who pointed out the market’s price mechanism is invaluable for aggregating and communicating information.

No central planner can ever replicate the price mechanism’s ability to give producers and consumers information they need to make the best decisions.

Lower prices, higher incomes

The character Toby Ziegler in The West Wing succinctly expressed the virtues of free trade and free markets more generally when he said (courtesy of Aaron Sorkin and his fellow writers) “it lowers prices, it raises incomes”.

In 1990 more than a third of the world’s 5.3 billion people lived in abject poverty, on less than US$1.90 a day.

Now about 9 per cent of the globe’s 7.9 billion people live in such poverty. That’s about 1.2 billion fewer people, an extraordinary testament to the power of markets.

Since 2008 – and during the coronavirus pandemic – the limitations of free markets have come into sharp relief. More – much more – needs to be done to make markets fairer. That means a commitment to the dignity and freedom of all.

But it also means a commitment to the hard work of building a more prosperous society, not just shrieking from the sidelines, complaining about the things that are wrong, and misidentifying the solution.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Richard Holden is Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School. His research focuses on contract theory, law and economics, and political economy. He has also written papers on political districting, the boundary of the firm, incentives in organisations, mechanism design, and voting rules.