The kids are alright

It would be easy to believe, if you pay attention to the media, that Australian children are in poor shape.

Kids, we are told, have too much screen time, too little exercise, too many scheduled activities and not enough risk and freedom. Earnest commentators constantly critique “helicopter parenting”, “tiger mothers”, “intensive mothering” and “bubble-wrapped children”.

There is certainly some basis to these fears. But it’s also instructive to take an historical perspective, because while childhood has changed in important respects since the second world war, there are surprising continuities.

Every generation of elders has worried about “young people of today”, from the 1950s to the 2010s. Some of the changes to childhood and parenthood could even be characterised as positive. So how has the idea of childhood, and the relationship between children and parents, changed since the 1950s?

The boomers’ parents worried about them too

From its earliest days, a baby of the 1950s usually had a single maternal figure as primary caregiver. Women were expected to become mothers and homemakers, whereas men were expected to be breadwinners and less involved in childcare.

Some valued this gendered division of labour, while some mothers felt restricted by cultural expectations, and some fathers possibly regretted their limited role in their children’s upbringing.

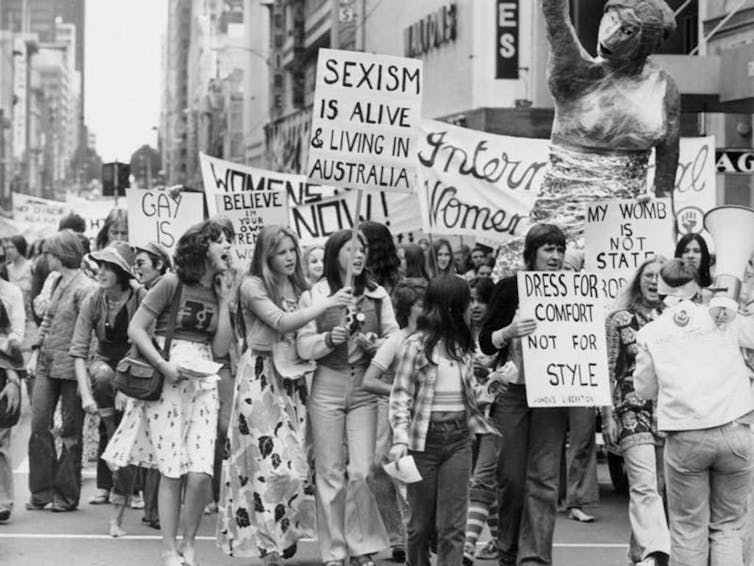

Women’s liberation in the 1970s overturned the idea that mothers would devote themselves solely to child-rearing.

The women’s liberation movement overturned such assumptions, stimulating increased maternal workforce participation. By the 21st century, expectations reversed, from a presumption that mothers didn’t work to an expectation that they did. In addition to their paid workload, contemporary women’s caring and domestic work increases dramatically after having children. The domestic division of labour is still far from equal.

Many fathers today want to be more involved in their children’s lives but feel constrained by cultural expectations and financial pressures. Australian families have also diversified, embracing new structures including single parents by choice, same-sex parents, blended families and more.

Child-rearing philosophies have certainly changed. Parents of the 1950s relied on informal advice from relatives and friends, whereas today parents can feel overwhelmed by the volume and contradictions of child-raising advice, delivered by health professionals and “experts” of more dubious qualifications.

In parallel to the women’s liberation movement, children’s rights began to be taken more seriously in Australia from the 1970s and were given international legal status under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of the Child in 1989. Such shifts led to a greater interest in children’s perspectives and emotions. For example, corporal punishment is now widely frowned on and has been banned in schools.

Whereas post-war child-rearing emphasised discipline and routine, parent-child relationships in 2020 are more emotionally expressive, relational and intense.

With the popularisation of psychology, childhood became viewed as the critical phase for emotional growth. Parents, particularly mothers, continue to bear a weighty responsibility for healthy child development.

Despite changes in child-rearing approaches, every generation of Australian parents has tried to do their best for their children. Parental love is constant.

We also expect more emotionally from children. Many post-war children rarely left their mother’s care until kindergarten, whereas today many Australian preschoolers experience some non-maternal care. In 2011, three-quarters of Australian mothers returned to paid work by the time their child was 13 months old, on average resuming when their child was 6.5 months old.

From being a rarity in the 1950s, childcare centres have multiplied. Shifts in caregivers represent rising emotional expectations of preschool children: that they should be able to tolerate separation from their primary caregiver and behave appropriately in a social and learning setting.

As children have gradually spent more time in childcare, preschool, primary school and secondary school, adults outside the family have a greater influence in a child’s life.

Shrinking childhood freedom?

Remembering their postwar childhoods, baby boomers emphasise their freedom to roam as long as they were “home by dark”. Children’s independent roaming has shrunk in urbanised societies across the world since the mid-20th century.

But there is plenty of evidence that post-war adults still feared for children’s safety, worrying about poisonous chemicals around the home, and teachers were concerned about “stranger danger”, traffic accidents and dangerous toys.

Baby boomers also recall “making their own fun” without elaborate toys or adult-organised activities. They remember playing scratch footy with a paper ball, swimming in ponds and creeks, and exploring wilder areas.

But, simultaneously, store-bought toys became more affordable to less-privileged families in the 1950s, as new materials and mass production reduced prices. And while kids today doubtless have more “stuff”, they still enjoy constructing sandcastles, climbing trees and creating cubbies with sticks and leaves.

The dangers of screen time for young children and the risks of online bullying or abuse generate enormous anxiety in parents today. Yet every generation of parent has worried about children’s “downtime”. In the late 19th century, reading novels was feared to encourage precocious sexuality in young women. In the 1980s, parents warned their children that watching television would lead to “square eyes”.

Children of the 1980s will remember being warned too much television would give them ‘square eyes’.

Concern about tablet or smartphone use among preschoolers follows a long tradition of parental anxiety about the impact of new technologies. While social media can certainly host antisocial behaviour, digital communications can also connect young people across geographic distance and overcome social barriers like mobility issues or vision impairment.

While more instances of anxiety and depression are being identified in children and teenagers, this does not mean mental illness is actually increasing.

These days, parents are more likely to initiate dialogues about painful emotions and challenging relationships. Conversations between parents and children have become franker around many topics, including sexuality, puberty, body safety and dealing with difficult feelings. The emotional lexicon of the parent-child relationship has become more open and complex.

Not all Australians experience happy childhoods or loving families. A series of government inquiries have exposed shocking mistreatment of children, including those forcibly removed from their families, such as the Stolen Generations, and children abused while in the “care” of welfare institutions and religious organisations.

While the revelations of such abuse have been distressing, they indicate an important cultural shift in Australia. No longer will we allow abused children to repress their stories in secrecy and shame. Let’s hope these painful testimonies of past childhoods will help prevent the traumatising of future childhoods.

Australian childhood is in good shape

Concern about childhoods in the present is often a disguise for nostalgia about childhoods past. We nurture highly emotive associations with our memories of growing up, by virtue of the privileged place that childhood is seen to hold in the formation of adult identity.

While the details of childhood and parent-child relationships shift in different historical contexts, the fundamentals remain the same. Childhood is a time of learning, exploring, growing – and the appropriate way to grow is dependent on the cultural circumstances into which each generation is born.

Parents will always strive to do their best for their children. Constant collective concern and criticism only increase parental anxiety and hyper-vigilance, exacerbating the “lawnmower parenting” and “hothouse children” that stimulated the concern in the first place.

This article was published by The Conversation.

Carla Pascoe Leahy is an Australian Research Council DECRA Fellow at the University of Melbourne. Her research focuses on the history and heritage of childhood, menstruation and motherhood in twentieth-century Australia.