The business reality of baby dreams

“I think they collected […] maybe, six eggs. I think we got four embryos out of that […] One was transferred and three were frozen. So, the fresh cycle didn’t work. Tried a frozen one, didn’t work. Went to try the third frozen and they told me that one didn’t survive unfreezing, so then we had one left and that didn’t work, so we had no embryos left. So we did a fresh egg cycle again, and they got even less this time […] So I was thinking this is all going to be wasting time. But […] I think they fertilised four eggs, and then there was only one viable one, which is my baby.”

Eva, a teacher in her early 30s, describes in my recent book The Oocyte Economy: the Changing Meaning of Human Eggs, a very common experience for women who have fertility treatment.

Many women and couples, encouraged by success stories and marketing, hope their years of unsuccessful attempts to conceive a child naturally are over, and fertility treatment will work.

Assisted reproductive technologies cover a range of procedures, including in vitro fertilisation or IVF. And they are big business. Australia’s fertility industry is estimated to generate revenues of A$550 million a year and A$630 million by 2022. Some of the biggest clinics are publicly listed companies.

Globally, the industry is estimated to be worth US$25 billion and is predicted to grow to US$41 billion by 2026.

But it’s easy to forget that before the business of IVF, human egg cells were just that — cells. Not an entity to be manipulated in the laboratory, not something to be bought or sold, not a valuable commodity that crosses international borders.

The story of how human eggs went from cells to valuable commodity starts in a unlikely place: the sex lives of farm animals. How far the commodification of human eggs will go is up to us, as a society, to decide.

How did we get here?

From the 1920s, farmers used techniques like artificial insemination for their animal herds. And from the 1950s, scientists in the US, UK and Australia developed in vitro fertilisation techniques to harvest eggs from rabbits, mice, sheep and dogs, fertilise them in a laboratory, then implant the embryos into the uterus (womb).

The birth of healthy animals through these techniques reassured some doctors and scientists the approach could be adapted for humans.

But it took over 20 years of experiments and failed treatments, involving thousands of women, before the first IVF baby was born, Louise Brown, in 1978.

Louise Brown, the first IVF baby, made headlines around the world when she was born in 1978.

At first, IVF was controversial. After Pope Paul VI condemned it in 1968, Catholic bishops in Australia, the UK and the US said IVF was contrary to moral and natural law. Some feminists condemned IVF as experiments on “test-tube women”.

Eventually, the controversy died down. In 2017,a total of 14,882 babies were born in Australia through assisted fertility technology, including IVF.

Human eggs are bought and sold, both interstate and internationally

Since the early days of IVF, human eggs have become valuable commodities, but in many different ways.

Australia’s Medicare subsidises fertility treatments for couples diagnosed with medical infertility. But there are few public fertility clinics. So most people go to private clinics, at considerable expense.

At Australian private clinics in 2018, patients paid an average A$3,500-$5,000 per stimulated cycle (from hormone treatment to egg collection).

By the time you’ve added fees for anaesthesia, embryo storage and other costs, patients can spend tens of thousands of dollars if they have more than one cycle.

Then there’s the market for eggs. In some parts of the world, women who cannot conceive with their own eggs can buy someone else’s. This service is also used by gay or straight couples when engaging a surrogate.

If you live in California, New York, and many other states in the US, you can buy eggs from young women, usually students trying to pay for tuition or student debt, in your own state.

Usually a woman will ovulate one egg per menstrual cycle. But if she is donating eggs, she can take medication to produce several eggs at once.

A cycle of eggs costs US$6,000-$15,000 depending on the qualities of the egg provider and where the clinic is. If the donor is athletic, beautiful, musical and has good university grades, she may be able to command a higher price.

If you live in Australia, it is illegal to exchange money for eggs. However, eggs can be donated, in the same way that blood or kidneys are donated: as a gift. Donors may be compensated for direct expenses.

As egg donation is a difficult, time consuming medical procedure, few Australian women are prepared to donate them. In Australia in 2017, 983 cycles (from hormone stimulation to egg collection) were carried out on women prepared to give their eggs.

Then there’s the international market for eggs. This is when women and couples from more restrictive countries such as Australia, Germany or France, which prohibit egg purchase, can contact clinics overseas in countries that are less restrictive, like some states in the US, Spain and South Africa.

They can arrange to buy eggs from younger, more fertile, and generally poorer women, and have IVF in an overseas clinic. As couples travel to escape national regulation, there are no reliable estimates of the market value of this cross-border fertility travel.

Eye colour, hair colour and ethnicity: the many ways you can shop for eggs.

Couples generally want a donor who resembles them, as they often don’t want others to know that their child is not their genetic offspring. So clinics specialise in matching patients’ looks and colouring (for instance, blue eyes, black hair, tall).

In some places, like California, patients can request a range of other qualities (a doctorate, for example), if they are prepared to pay for them.

The big freeze

Since about 2010, women have been encouraged to freeze their own eggs while young (and fertile) to thaw and use years later when their fertility would otherwise decline.

This “personal” or “social” egg freezing is different to freezing eggs for medical reasons, when women undergoing cancer treatment have their eggs frozen beforehand, as chemotherapy and radiotherapy can destroy egg fertility in even very young women and girls.

Women have been encouraged to freeze their eggs for personal or social reasons, rather than for medical ones. But it’s costly.

Fertility clinics now offer personal egg freezing as a standard service. Clinics generally don’t advertise the cost of egg freezing directly. But at the clinic in London where I interviewed women who had frozen their eggs, the cost per cycle was £6,000 and £500 for annual storage.

In Australia it is estimated to be around A$10,000. Women may be advised to have two or three cycles, depending on their age. The older they are, the less likely any individual egg will be fertile.

The take-up for personal egg freezing is increasing every year. In 2015 in Australia and New Zealand, there were 1,213 egg-freezing cycles. By 2017, there were 2,113.

In Victoria in 2018, 2,411 women had frozen eggs in storage, and 134 cycles of IVF used previously frozen eggs.

A ‘smart, stylish career-girl move’

Egg freezing for personal or social reasons has become a popular topic in women’s magazines, like Vogue and Glamour, where the prospect is framed as a smart, stylish career-girl move.

In 2014, the media reported how Google, and other big technology and law firms, offered egg-freezing to its new female staff as part of their remuneration package.

In the US, where maternity leave is not mandatory, an egg freezing package means women can delay having children until their careers and finances are more established. The idea is they can use their frozen eggs in their 30s or 40s to conceive.

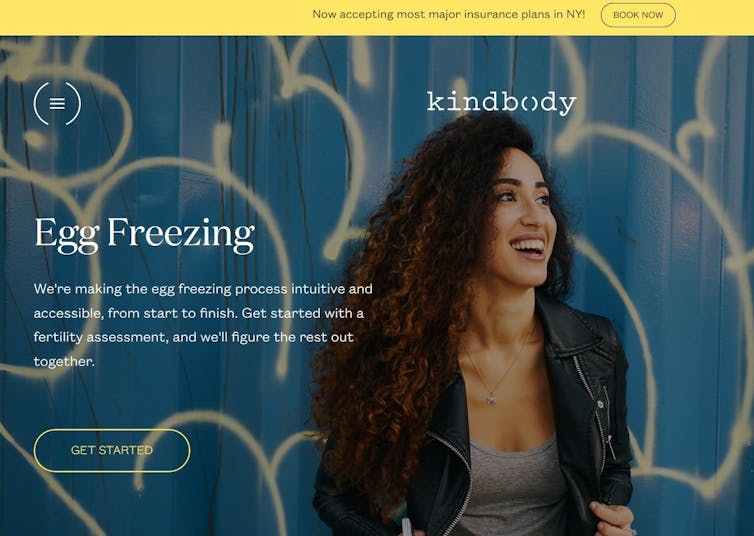

In a more recent development, egg freezing “boutiques” in the US are challenging the fertility clinic sector for what is seen as a more and more lucrative business.

These facilities include spa treatments, in house vitamin supplements and yoga classes. They’re attracting both venture capital and women’s fees.

This egg freezing boutique in the US targets younger women.

Women in their 20s and 30s are persuaded, at glamorous information nights to use these facilities.

The boutiques even offer fertility loans to younger clients, who lack the disposable income of their older ones.

Clients go into debt for frozen eggs they may never use. We can see how 20-something women could readily end up with student loans and egg freezing debts, making it even harder for them to become financially independent.

It’s unclear whether boutique private egg freezing clinics could be set up in Australia.

No wonder women need help conceiving

For many women, by the time they finish university education, establish their careers, find a partner and create a stable household before they can consider children, time has marched on.

As housing becomes less affordable, people are studying for longer and the demands of the workplace escalate, it becomes more and more difficult for women to have children when their eggs are fertile, during their 20s or early 30s.

As more women choose later childbearing, they look to fertility clinics and egg freezing as a way to manage their dwindling fertility.

However, once they start treatment, women rapidly discover no medical procedure can compensate for declining fertility of their own eggs. IVF can produce more eggs in a cycle than women routinely produce via normal ovulation (that is, one). However, it cannot make eggs themselves more fertile.

We know that women’s fertility declines after the mid-thirties. So IVF success rates drop rapidly by the age of 40, and by 45, conception with women’s own eggs is very rare.

As eggs become more and more precious, women will pay well, if they can, to preserve and manage them. If that’s not possible in their home country or state, the hunt for eggs can take them overseas or interstate, again for a price.

More public fertility clinics, as recommended by a recent Victorian report, might change the landscape. The same report recommended a public sperm and egg bank.

Such moves might give women access to evidence-based treatments without running up huge bills. It might provide fertility preservation services that are less likely to send clients into debt and less likely to be driven by the need to pay dividends to shareholders or return profits on private equity. A public egg bank might also encourage altruistic egg donation, although the demanding nature of such donation will always remain.

However, the very best way to decommodify eggs, would be to have social policy that supports women who want children to conceive before their fertility declines. More generous and extended maternity leave would be a good start.

This article was published by The Conversation.

![]()

Professor Catherine Waldby is Director of the Research School of Social Sciences at the Australian National University, and Visiting Professor at the Department of Social Science and Medicine at King’s College London. Her research focuses on social studies of biomedicine and the life sciences.