Stumbling into the brave new world of gene editing

Editing the human germline is going to happen in the near future. I want to remind everyone that we should proceed slowly and with caution. Because a single case of failure could kill the entire field.” He Jiankui, 2017.

For decades, humans have imagined a time when we could directly change our heredity. Now, this epoch has been ushered in with a self-fulfilling prophecy.

In 2017 He Jiankui, an Associate Professor from Southern University of Science and Technology in China, warned the gene-editing community it could be compromised through a single case.

Merely one year later, he has provided it.

Presenting his findings at the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing, Dr He claims that twins, Lulu and Nana, are the first humans to have their genomes intentionally modified.

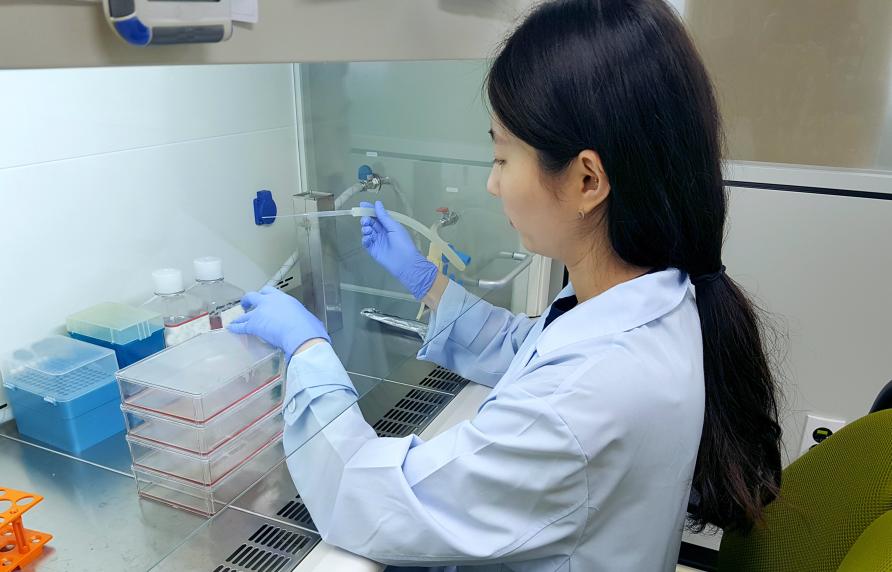

The twins have a healthy mother, Grace, but their father, Mark, is HIV positive. Grace and Mark were offered free IVF treatment, if they allowed any embryos created to be modified with the genome editing tool CRISPR-cas9. The intention of using CRISPR was to give the twins a resistance to HIV, although it’s unclear whether this was successful.

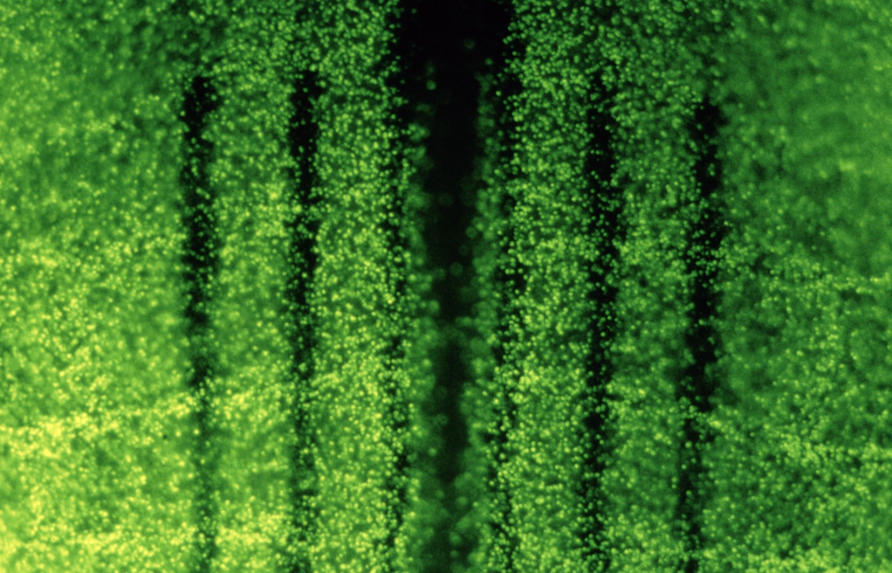

While many predicted that CRISPR would one day be used in reproduction, the speed at which it has happened is astonishing. Genome editing was essentially unheard of until a few years ago. Most of the interest in using CRISPR in humans has focused on assessing its safety and potential in treating adults who are already sick.

However, there are no approved gene-therapy projects currently using CRISPR, because of its unpredictable nature, and its use in reproduction is nearly universally seen as premature.

Dr He’s study has been roundly criticised as ‘unethical’, ‘reckless’, and ‘monstrous’ – but in order to learn from it, we have to be clear about these specific ethical failures.

Balancing the risk

Dr He’s experiment ignores a decades old consensus in research ethics – that is, any risk that research participants are exposed to must be balanced by appropriate benefits.

And it’s not clear that the twins have benefited in any sense as a result of the procedure.

Even assuming the twins have become resistant to HIV, which is highly questionable, HIV is now treatable through antiretroviral drugs. Also, while the number of cases of HIV in China is increasing, nobody can predict which diseases will be common in China in 20 years.

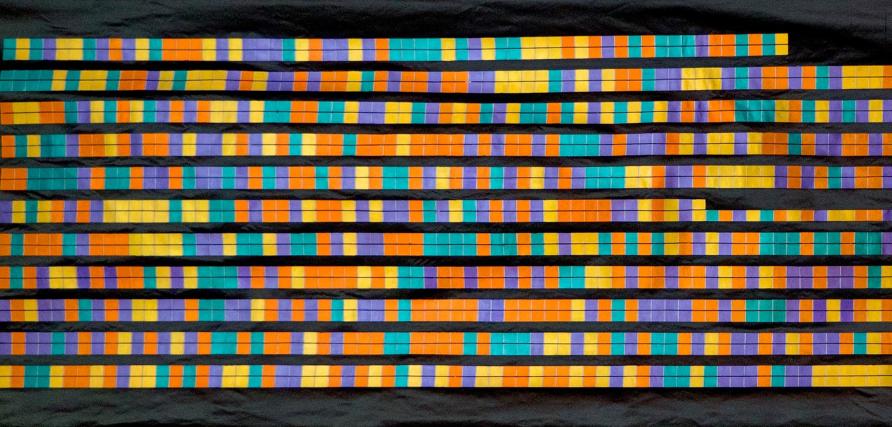

Dr He’s work focused on a gene called CCR5, which the HIV virus uses as a doorway for infiltrating human cells. Disabling CCR5 also makes people more susceptible to other diseases including influenza and West Nile virus – both of these diseases are more difficult to avoid than HIV.

So for only a very marginal benefit, the twins have been exposed to serious risks. As highlighted by other leading scientists at the Gene Editing Summit, CRISPR can still cause unpredictable outcomes like cancer or other diseases later in life.

When we’re conducting research, part of our job is to minimise risk as much as possible.

That’s why the first clinical application of gene editing in humans should be to reverse mutations which cause diseases that are lethal in childhood, like Tay Sachs and Leigh Syndrome.

That way, the relative cost of any side effects would be small. If Lulu or Nana die in early childhood, the procedure will have cost them a chance at a long and healthy life

Understanding the dangers

It’s highly questionable whether the trial participants knew what Dr He’s study involved.

We know now that the first sentence of the consent form given to participants refers to the study as an “AIDS vaccine development project”. This gives the impression that Dr He’s study was far less novel and risky than it was.

But the form itself is also full of technical jargon like “optimised optical sgRNA”, “ovarian reserve function” and “neonatal malformations” that would baffle even educated people.

It’s also important to note that HIV positive patients are a vulnerable group who may be less able to accurately weigh the potential costs and benefits of participating in a trial.

HIV-infected men can reduce the risk of passing the virus onto their children by using IVF. But these treatments are expensive in China and out of reach to many.

It seems likely that many couples in Dr He’s study wouldn’t have wanted their embryos to be experimented on, and took part merely to access IVF.

So having their children engineered was not really an autonomous choice. This could have been avoided if Dr He had offered all the recruited couples free IVF, and only then asked if they wanted to have their embryos altered by CRISPR technology.

Making information available online

But perhaps the biggest concern is the lack of transparency.

The study was first approved in March 2017. The announcement was only made after the twin girls were allegedly born healthy. It’s seriously concerning that scientists can secretly conduct such experiments.

Would we even know about the existence of Lulu and Nana if things had turned out badly? How many other gene-editing experiments are being performed that are hidden from view?

What Dr He’s study does is highlight the fact that global cooperation and transparency is vital for the successful development of gene editing.

To avoid another case like this, the human gene pool needs a global lifeguard.

This article was published by Pursuit.

Christopher Gyngell is a Research Fellow in Biomedical Ethics at the University of Melbourne. His research interests include the ethical implications of biotechnologies and the philosophy of health and disease.