Son of sequel – Has Hollywood run out of ideas?

Of the broad range of criticisms levelled against remakes, a popular accusation made by critics and commentators is that such material fails to justify its existence.

This line of attack usually takes two forms: a remake is overtly accused of being unnecessary, alternatively critics ask why bother or what’s the point?

Elisabeth Moss in The Invisible Man, a new take on HG Wells’ 1897 novel.

Recurrent in discussions on remaking is the argument that Hollywood has run out of ideas: that the industry keeps remaking itself because the creativity cupboard is bare.

Guardian journalist Jeremy Kay laments that “there are few sorrier manifestations of this dearth of ideas than the remake.”

Christopher Stevens in the Daily Mail argues a similar case: “in the past decade, 90 per cent of the most popular films have been based on earlier movies, comic books or novels. It seems no one in Hollywood now has an original notion in their heads.”

The subtext to such conjecture is a belief that studios should be pursuing “new” material because – according to popular wisdom – only new ideas are creative and only creative ideas are worthwhile.

Aside from the obvious impossibility of agreeing on a definition of what constitutes “new” in the context of storytelling – or even, for that matter, what “creativity” looks like – it also overlooks that some of the most significant contributions to film history have been made by completely unoriginal stories.

The Wizard of Oz (1939) is a perfect illustration of this: the story, based on the works of Frank Baum, was first filmed in 1925.

The 1938 film of the Wizard of Oz has overtaken Frank Baum’s books to become the version of the stories beloved by the public.

The 1939 reproduction, however, is the masterpiece celebrated today and thus demonstrates that when a film is critically acclaimed or beloved by audiences, no one really cares – or even remembers – that it’s a remake and that remakes can, of course, be beloved as well as creative and highly innovative.

Commentators frame the uncreative accusation in several ways, frequently dipping into the pool of negative remake rhetoric. One of the most popular examples of this is the accusation that material has been “warmed over.”

The warmed-over allegation alludes not only to a lack of creativity but, more so, to a distinct lack of freshness, if not overt staleness.

By using a phrase more commonly associated with food, the negative subtext is that audiences are being served up a “reheated” version of something they’ve consumed before, in turn implying that they are getting something less new and less good and paving the way for audiences to potentially feel insulted by such releases.

Such criticisms are evidence of remakes as a production category being dismissed as patently commercial, as lacking in creativity and originality and as not being culturally generative.

Remakes are under a unique kind of pressure that rarely gets directed at other screen content: such productions are expected to make a convincing case to audiences that they are worth seeing even though their content is not “new.”

Frank Herbert’s iconic science fiction book Dune has now been made into a film for the second time, as well as a recent TV series.

The argument that Hollywood is less creative today – or that it has somehow “recently” ran out of ideas – is premised on a nostalgic notion of a glory days when Hollywood was imagined as constantly churning out original and critically-acclaimed work.

From Hollywood’s very beginning, rather than an endless procession of wonderful new stories, studios were, in fact, producing adaptations of classic literature and stage plays, and, with every advent of new technology it was remaking its old properties.

Hollywood has always remade content while at the same time producing new(er) material. The American film canon is populated by both new stories and new versions of old ones.

But remakes can actually be creative, even when their stories aren’t totally “new.”

There are auto-remakes – where directors remake their own content – as well as the content of other filmmakers in an attempt to put their own unique stamp on an already- filmed story.

There are remakes of bad films or expanding on an existing property with deeper characterisation and a reimagined setting.

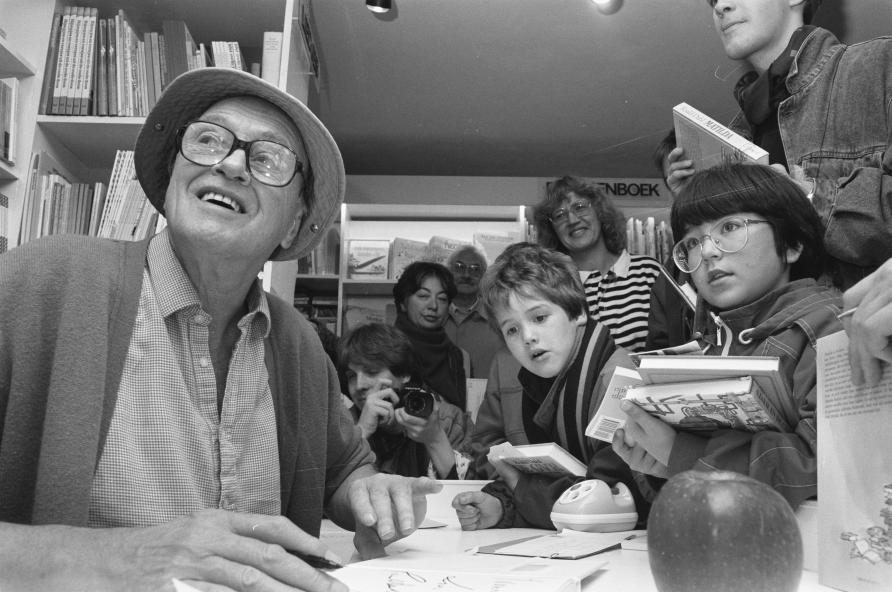

The Witches, the 1983 children’s book by Ronald Dahl, is being made into a film by Robert Zemeckis.

Remakes also become creative through more wholesale changes. This can involve swapping the genre – turning a thriller, for example, into a musical – or by targeting an entirely new audience, perhaps re-adapting a piece of classic literature as an animated children’s film.

Hollywood has been remaking on screen for over a century now, and yet critics and audiences still systematically condemn this material as though remade film and television is somehow a contemporary scourge, uniquely commercial and somehow more of a cash-grab than everything else made by big studios.

But if remakes are routinely criticised as cash-grabs and as uninspired, unnecessary, slavish, painful and insipid, why do they keep being made?

Equally, if audiences hate them so very much, why do they keep paying to see them, in turn guaranteeing further reproduction?

Until this dynamic alters, remake production will continue, regardless of claims that we’ve had enough.

This article an edited extract of Dr Lauren Rosewarne’s new book Why We Remake: The Politics, Economics and Emotions of Film and TV Remakes published by Routledge. It’s available now online or wherever books are sold. The article was published by Pursuit.

Dr Lauren Rosewarne is a Senior lecturer in the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Melbourne. Her research interests include feminist politics, media and communications and public administration.