Scroogled

The Federal Court has found that Google misled some users about personal location data collected through Android devices for two years from January 2017 to December 2018.

The Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (ACCC) says this decision is a “world first” in relation to Google’s location privacy settings. The ACCC now intends to seek various orders against Google, including pecuniary penalties under the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), which could be up to $10 million or 10 per cent of local turnover.

Companies should be warned that representations in their privacy policies and privacy settings could lead to similar liability under the ACL. But this won’t be a complete solution to the problem of many companies concealing their data practices, including the way they share consumers’ personal information.

How did Google mislead consumers about their location history?

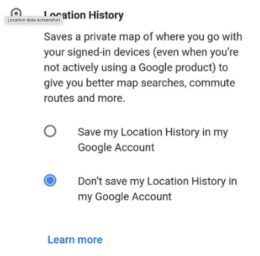

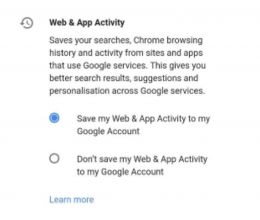

The Federal Court found that Google’s previous ‘Location History’ settings would have led some reasonable consumers to believe that they could prevent their location data being saved to their Google account. In fact, selecting ‘Don’t save my Location History in my Google Account’ alone could not achieve this outcome.

Users needed to change an additional, separate setting to stop that location data from being saved to their Google account. In particular, they needed to navigate to ‘Web & App Activity’ and select ‘Don’t save my Web & App Activity to my Google Account’, even if they had already selected the ‘Don’t save’ option under ‘Location History’.

ACCC Chair Rod Sims responded to the Federal Court’s findings, saying:

“This is an important victory for consumers, especially anyone concerned about their privacy online, as the Court’s decision sends a strong message to Google and others that big businesses must not mislead their customers.”

Google has since changed the way these settings are presented to consumers but is still liable for the conduct the Court found was likely to mislead some reasonable consumers for two years in 2017 and 2018.

ACCC has misleading privacy policies in its sights

This is the second case in which the ACCC has recently succeeded in establishing misleading conduct in a company’s representations about its use of consumer data.

In 2020, the medical appointment booking app, HealthEngine, admitted it had disclosed 135,000 patients’ non-clinical personal information to insurance brokers without informed consent of those patients. HealthEngine paid fines of $2.9 million, including approximately $1.4 million relating to this misleading conduct.

The ACCC has two similar cases currently in the wings, including a further case in respect of Google’s privacy-related notifications and a case about Facebook’s representations about Onavo, a supposedly privacy-enhancing app.

In bringing proceedings against companies for misleading conduct in their privacy policies the ACCC is following in the footsteps of the US Federal Trade Commission which has sued many US companies for misleading privacy policies.

Will this solve the problem of confusing and unfair privacy policies?

The ACCC’s success against Google and HealthEngine in these cases sends an important message to companies that they must not mislead consumers when they publish privacy policies and privacy settings. And they may receive significant fines if they do.

However, this will not be enough to stop companies from setting privacy-degrading terms for their users, if they spell them out in the fine print. Such terms are currently commonplace, even though the majority of consumers are increasingly concerned about their privacy and want more privacy options.

Consider the US experience. The US Federal Trade Commission brought action against the creators of a flashlight app for publishing a privacy policy which didn’t reveal that the app was tracking and sharing users’ geolocation information with third parties.

However, in the agreement settling this claim, the solution was for the creators to rewrite the privacy policy to disclose that its users’ geo-location and device ID data are shared with third parties. The question was not whether this practice was legitimate or proportionate, but having regard to the purpose of the app.

Major changes to Australian privacy laws will also be required before companies are prevented from pervasively tracking consumers who do not wish to be tracked. The current review of the Federal Privacy Act could be the beginning of a process to obtain fairer privacy practices for consumers, but any reforms from this review will be a long-time coming.

Dr Katharine Kemp is a Lecturer at the Faculty of Law at UNSW Sydney. Katharine’s research focuses on competition law, particularly misuse of market power, consumer protection and data privacy in financial services regulation.