Platform pitfalls

The power of platforms to suggest content we may like is a boon for convenience, but secrecy around data collection raises troubling questions.

Billions of people receive recommendations from digital platforms that impact on their daily offline life. What series they binge next, where they go on holiday, their next favourite song and the people they date are often shaped by the algorithmic curation of digital platforms.

Platforms need to know as much as possible about their users in order to make these recommendations. But the full extent of the data that companies collect and use is still largely a closely guarded secret.

Recent research has found that Spotify and Tinder are extracting an ever-growing amount of data from users. Through an analysis of successive versions of the platforms’ terms of use and privacy policies, the research shows the growing types of data taken: in Spotify’s case, photos, location, voice data, and personal information like payment details are being collected.

Both companies vaguely list the types of user data they collect – in Spotify’s case, data “for marketing, promotion, and advertising purposes”. But why would a platform like Spotify use voice data? On its website, the company lists several reasons for collecting various types of data, but these explanations, like many other platforms’, are vague and open to interpretation.

But even if the reasons were clearly stated, there is no way of knowing whether what we’re being told is true. The underlying code driving the algorithms is protected and platforms are under no legal obligation to share it.

In its 2021 policy, Spotify explicitly said that some user data is used in its recommendations. The company reserves the right to “make inferences” about users’ interests, and says “the content [users] view” is determined not just by their data but by Spotify’s commercial agreements with third parties. What Spotify markets as highly personalised, tailored content is influenced by factors outside users’ listening data, including agreements with artists and labels.

This two-pronged approach is a pincer movement: an exploitative strategy that simultaneously attacks user privacy and rights while defining their tastes, choices and identity. The first movement is about extracting as much data and information from users as possible. Once this data is processed, the second movement is about conditioning users’ online and offline behaviours.

The opaque way in which digital platforms collect and use user data demonstrates how power can be enacted through technology by monitoring, guiding and adjusting behaviours in subtle ways.

In the unregulated corners of cyberspace, digital platforms are not obliged to share their functionalities.

Relatively free of legal restrictions, companies that collect data consolidate their power to do so in a few ways. Companies unilaterally decide upon their own terms and conditions and privacy policies, and these can be changed at any time.

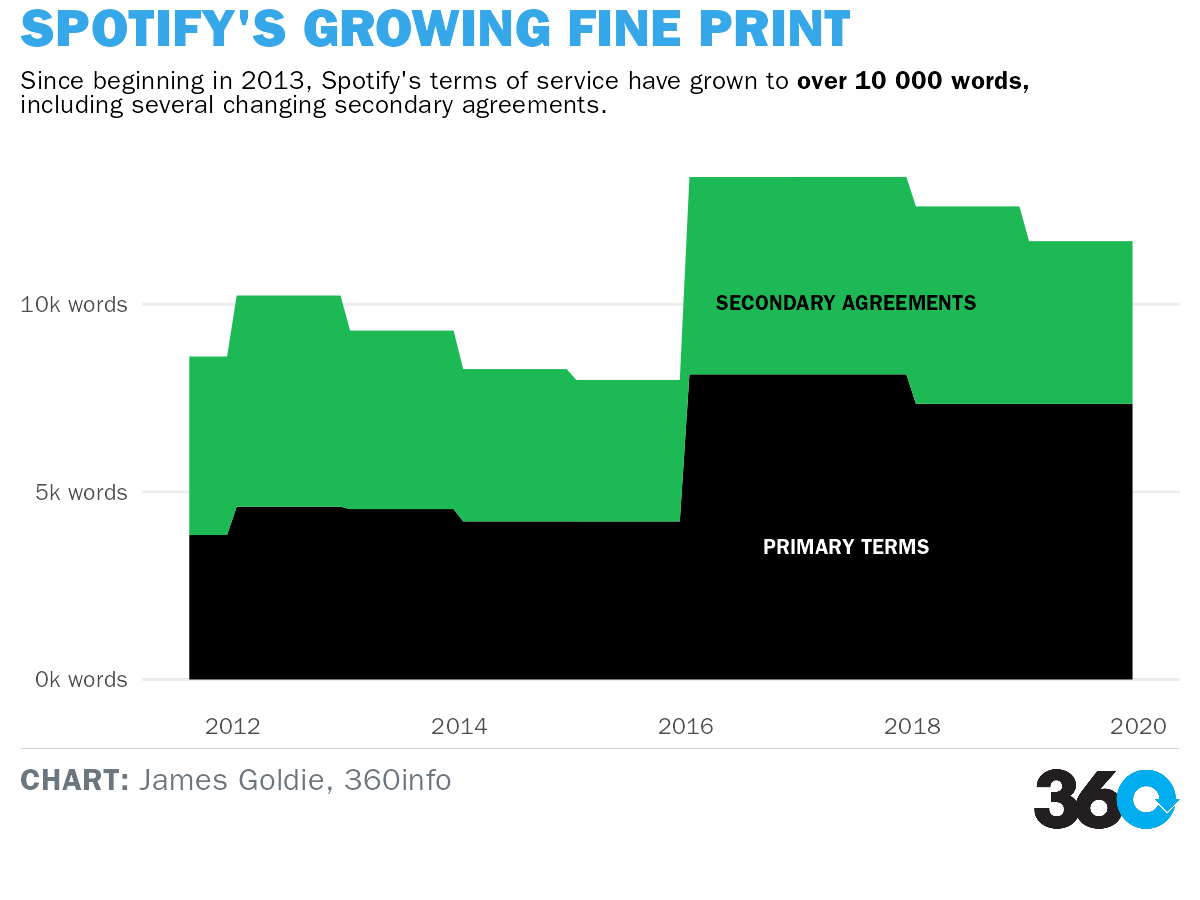

Since beginning in 2013, Spotify’s terms of service have grown to over 10 000 words, including several changing secondary agreements.

Software updates can create new norms for using the app. For example, in 2019 Spotify drastically changed the user interface so that users had less control over the music they could listen to. Users were told the update was “fixing performance issues”, but the new version made changes that removed features, reducing users’ ability to navigate their libraries.

Regulatory intervention may be the only viable solution to initiating or restoring a more democratic cyberspace. The European Union is already taking steps in this direction. On 22 March 2022, the European Parliament and Council approved a Digital Services Act (DSA) to “create a safe and accountable online environment”.

The DSA touches upon the need for platforms to be held to account for their societal impact, outlining a number of obligations for digital platforms that seek to operate in Europe, such as transparent reporting, measures against abuse, and giving users the choice to opt out of recommendations based on profiling.

The DSA is one move towards more universal mechanisms that circumvent the secrecy around the operation of powerful digital platforms and the companies behind them. As more users know how much data is collected from them and start questioning why and how it is used, lack of transparency from companies will become less likely to be accepted.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Fabio Morreale is a Senior Lecturer at The University of Auckland. He has a PhD in computer science and his current research investigates the cultural, political and ethical impact of artificial intelligence in the creative arts.