New ports of call for Australian goods

China’s share of Australia’s trade—both exports and imports—is falling and is being replaced by other trading partners in Asia, bringing important diversification to Australian markets.

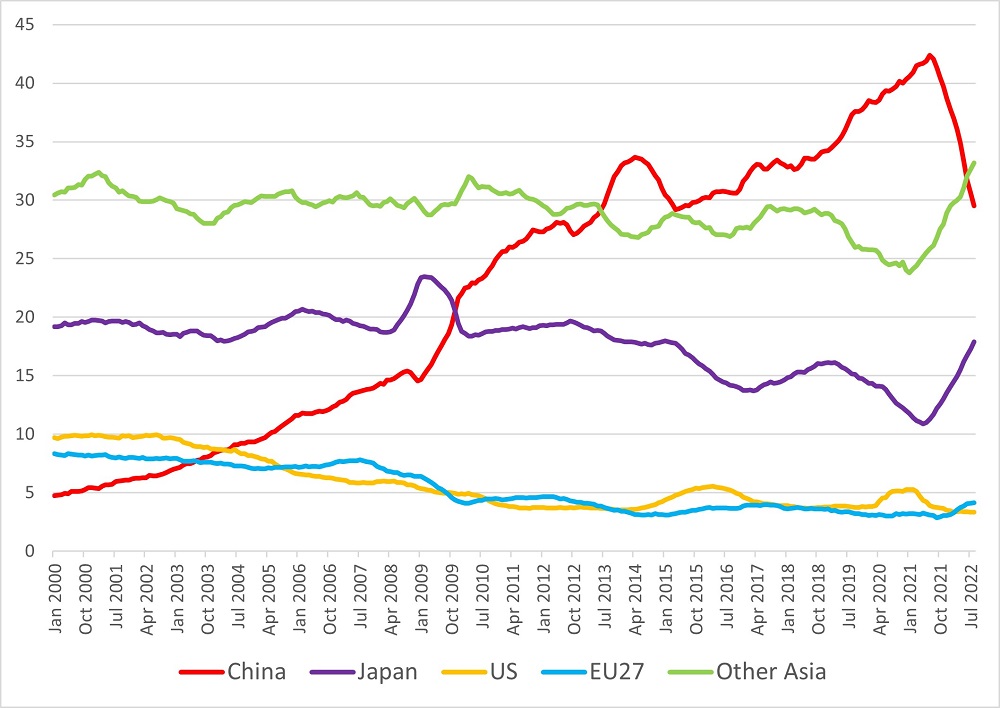

The latest Australian Bureau of Statistics trade report shows that China’s share of Australia’s exports, which peaked at an extraordinary 42.1% a year ago, was down to 29.5% in the 12 months to August.

It is the first time China’s share of Australia’s exports has dropped below 30% in a 12-month period since October 2015 and reflects the impact of the Chinese government’s efforts to punish Australia for perceived slights by erecting trade barriers, as well as the decline in the iron ore price.

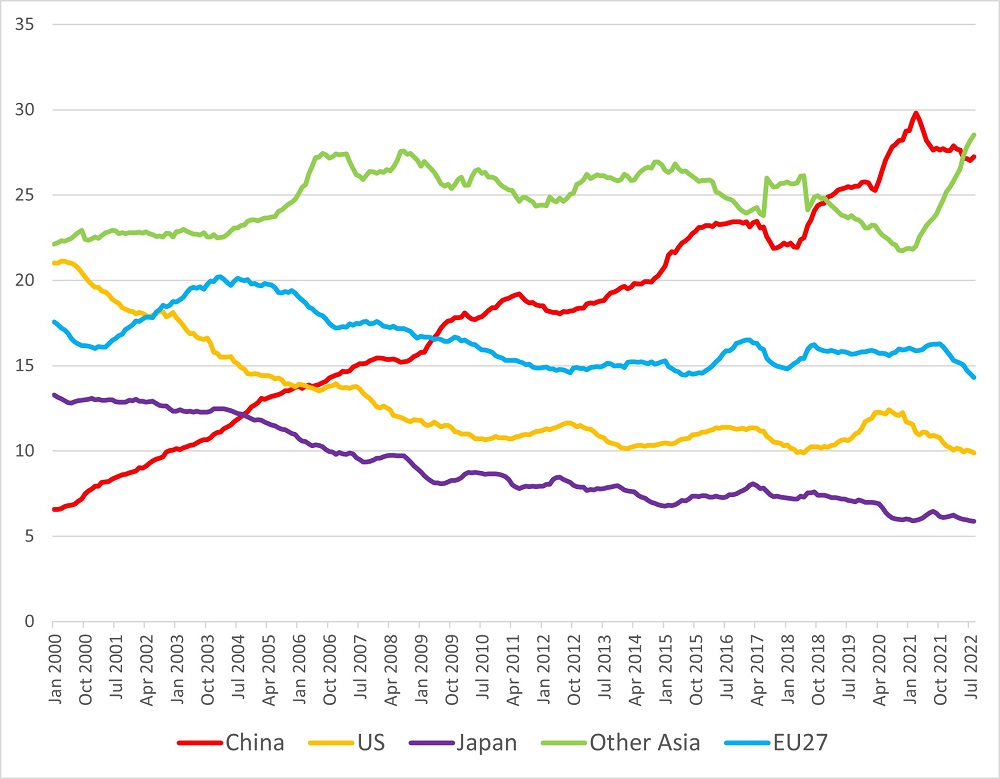

More surprisingly, China’s share of Australia’s imports has also started to fall as Australian companies seek to diversify their suppliers. China’s share of Australian imports peaked at 29.8% in the 12 months to March 2021, but had slipped to 27.2% in the year to August. In the past three months, its share was 25.9%, indicating that the trend decline is continuing (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Australia’s import sources (%)

Source: ABS trade data.

Japan has recovered ground as a market for Australia’s exports while, for both exports and imports, the rest of Asia—principally South Korea, India, Taiwan and the ASEAN group—now accounts for a larger share of Australia’s trade than China. That ‘other Asia’ collective (excluding Japan) now takes 33.2% of Australia’s exports and provides 28.5% of its imports (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Australia’s export markets (%)

Source: ABS trade data.

This reordering of Australia’s trade partners brings greater balance to the nation’s trade profile, which had become extraordinarily focused on China.

Australia had not been as dependent on a single market since 1938, when it was the ‘mother country’ of the United Kingdom. Japan’s share of Australia’s exports peaked at 33.4% in 1976. Although Australia’s trade with Japan hasn’t always run smoothly, it was never adversarial as has been the case with China since 2020.

On the import side, the UK is the only trading partner to have provided 30% or more of Australia’s supplies.

China’s rise as Australia’s principal trading partner was rapid. When Kevin Rudd became prime minister in 2007, China represented only 14% of Australia’s exports and 15% of its imports.

China had an extremely resource-intensive burst of growth from 2003 until 2020 building mega-cities and vast infrastructure. Australia had both the mineral reserves and corporate know-how to respond to its demand, becoming its principal resource supplier.

China became the world’s biggest manufacturer, producing almost as much as the United States, Japan and Germany combined, at the same time as Australia’s manufacturing shrank to just 5.6% of the national economy. The enthusiasm of both Australian and Chinese businesses for each other’s markets was fostered by the 2015 bilateral trade agreement, before relations soured.

Australia remains more exposed to China on both imports and exports than almost any other nation. For example, China takes just 6% of US exports, 11% for the European Union and 19% for Japan. China provides around 16% of the rest of the world’s imports.

The monthly ABS trade data covers the Australian dollar value of trade, not the volume of goods shipped, and so partly reflects changes in prices.

The volume of Chinese purchases from Australia would have started falling in April 2020, after then–prime minister Scott Morrison’s call for a global inquiry into the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic proved to be the catalyst for sweeping Chinese export barriers.

The value of exports hit a peak a year later because of soaring prices for iron ore, liquefied natural gas and coal. A fall in iron ore prices in recent months has contributed to the decline in China’s trade share.

The diversification since China started imposing trade barriers on Australia has been significant and underlines the importance of bilateral and multilateral relations across the rest of Asia.

China eclipsed Japan as Australia’s biggest single export market in 2009. Japan’s share of Australia’s exports had dropped to just 10.8% by May last year, its lowest level since 1955, long before the iron ore trade began. However, Japan’s purchases have increased, almost doubling in value over the past year. In the year to August, Japan’s share of Australia’s exports rose to 17.9%, the highest since early 2015.

Elsewhere in Asia, South Korea is becoming a much more important trading partner for Australia. Its share of exports has risen from 7.1% to 9.0% over the past year, while its share of imports has jumped from 3.5% to 5.7%.

India has helped compensate for the downturn in sales to China, with its share of Australia’s exports rising from 3.4% to 5.4%. Taiwan is also growing in importance, taking 4.7% of exports, up from 2.9% a year ago, and Australia is selling more to Vietnam and Malaysia.

The European Union, which is taking coal that used to be destined for China, has raised its share of exports from 3.0% to 4.1% over the past year, surpassing the US, which now accounts for only 3.3% of Australia’s goods exports. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade historical records show that the US share is the lowest since 1913!

Australian businesses are not turning to the US, Europe or Japan to diversify their sources of supply. The three major advanced economies all account for a smaller share of Australia’s imports than was the case two years ago. For the US and Japan, there is a long-term decline, reflecting the shift in consumer, electronics and motor vehicle manufacturing to lower-income countries in Asia. Collectively, the advanced nations now supply 30% of Australia’s imports, down from 40% 15 years ago.

Besides South Korea, the new competition for China in the Australian market is coming from Singapore and Taiwan.

To the extent that companies are seeking alternative suppliers to China, it reflects their own risk management. There is no official promotion of Australia as a marketplace, since the legal mandate of the trade-promotion agency, Austrade, restricts it to promoting exports and export-oriented foreign investment.

This article was published by The Strategist.

David Uren is a Melbourne-based business writer and investor relations advisor. He has been writing about business for the past 25 years for publications including The Australian, The Age and BRW.