Millennial bugs?

More than 20% of Australia’s COVID-19 cases are people in their 20s, and those in their 30s account for another 16 per cent. Accordingly, attention has recently turned to not just the rate of infection among young adults, but also the reasons for these disproportionate rates.

Depicted as selfish and reckless, the media and government discourse has lent hard on the idea that ‘apathy among young adults has mutated the coronavirus into a Millennial bug’.

I’m sceptical of ‘whole of generation’ assessments. They are convenient, but very blunt and often misleading. They tend to miss the mass of diversity within a generation, and also the ways that generations are similar to, and even connected to one another. And worst of all, this formulation of a ‘millennial bug’ is profoundly inaccurate.

Young adults have higher rates of infection, yes; but we need to keep a sense of proportion, because the virus affects people across the age spectrum. This gets lost when we situate young adults as being the overt, main risk category.

The early messaging at the other end of the scale, where there were suggestions that older sections of the population were more susceptible as well as vulnerable to more serious consequences, have in part led to a misunderstanding that young people might not get infected. This likely plays at least a small role in the consequent spike in infection among young adults.

Looking at the stats: What story do we want to tell

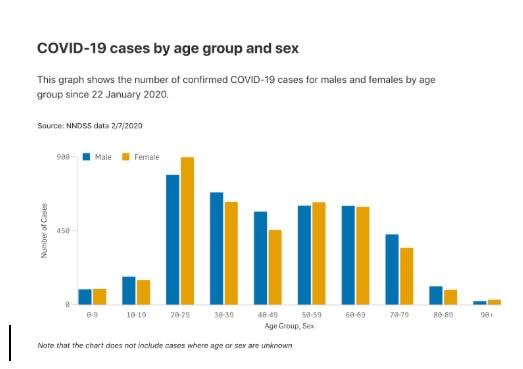

Coming back to the statistics, it’s important to stress that the story depends on how we cut and compare the data. At first glance, based on Australia’s infection figures at the time of writing, a dip off in numbers when we look at those in their 40s underpins the logic that leads health experts to suggest that those in their teens, 20s and 30s must do better in preventing community transmission.

‘Youth researchers have decades of evidence for this kind of storytelling, where young people are constructed as the folk devils of a moral panic.’

But looking at the graph below, the logic starts to feel a bit ropey. Cases among teenagers are a fraction of pretty much all the adult age groups, so their inclusion in this assessment of who needs to be more responsible lacks credibility.

Then let’s look at rates of infection among those in their 50s and 60s, which go back up close to where they are for those in their 30s. I suggest there are very few of us – and fewer news headlines – asking what it is about those in their 50s and 60s that makes them more virus-prone than those in their 40s. And we definitely are not saying ‘oh, these baby boomers are so much more likely to take risks than those in their 40s!’.

The contrasting gender gaps for those in their 20s relative to those in their 40s or in their 70s are also yet to get a look in.

As these questions and complexities in the data are ignored, the temptation to abide by the common-sense discourse that young people are inherent risk takers is propped up. The resulting current framing of the ‘millennial bug’ speaks to what is true of every generation: the young people of the time are held up in one way or another as a threat to themselves or others.

Youth researchers have decades of evidence for this kind of storytelling, where young people are constructed as the folk devils of a moral panic, where individual biological or psychological developmental stages are noted as drivers of risky behaviour.

Sociologists challenge these ideas about risk in ways that have relevance for the current discussion.

First, we question the idea of ‘objective risk’, and instead place emphasis on the social construction of risks. This allows us to understand that ‘risky’ behaviour is bound up with complex social processes and embedded in routine social practices.

Risk is a product of social reality, not just individual impulse

Using this logic, we can see that the spike in infection numbers among those in their 20s and 30s is bound up with very mundane social and economic realities: primary among these is that such groups are more likely to work in those fields with higher likelihood of human interaction – frontline work in the care sector, and especially in restaurants, bars and shops.

The latter are the landscapes of young people’s social lives, too. As the lockdown was relaxed and these places of work and leisure reopened, and people were allowed to frequent such places again, the spike among young adults seems less surprising.

Reckless abandon and selfishness is a more compelling or attention grabbing way to situate it, but I think that is a fabrication that does little more than stoke the flames of the so-called ‘generation wars‘.

Whole of generation’ assessments are convenient but very blunt, and often misleading, and overlook other significant social characteristics such as gender and class.This generational framing again overlooks the significance of other social characteristics. As above, the gender gap that sees women in their 20s more likely to contract the virus is barely discussed, while the issue of class has until now been largely absent.

Whole of generation’ assessments are convenient but very blunt, and often misleading, and overlook other significant social characteristics such as gender and class.This generational framing again overlooks the significance of other social characteristics. As above, the gender gap that sees women in their 20s more likely to contract the virus is barely discussed, while the issue of class has until now been largely absent.

Yet, the importance of class is so vividly illustrated through consideration of the first wave of Victorian suburbs that have been recently placed back in lockdown, as well as last weekend’s lockdown of nine Melbourne tower blocks.

What characterises these suburbs is not that they are comprised of mainly young people, but that they are predominantly low SES, multicultural areas populated by large numbers of people that work frontline jobs with human interaction.

Scapegoating young people won’t work

Whilst I reject the ‘young people are the worst’ narrative, there is good evidence that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to public health messaging, and engaging young people has been found to require more nuanced approaches across a variety of health domains.

So how do we get the messaging right if we are to target it at young people?

First, there is a need to get young people involved as citizen scientists in data collection and as co-designers of public health messaging.

Beyond that, or in its absence, the last couple of decades of youth research has made clear that young people often feel like they navigate the world, and all contemporary risks, in a more individualised way; there is less collective certainty than was apparent for generations gone by.

When you’re a generation told to feel the need to take control and responsibility for your whole life, a paternalistic tone just won’t cut it – authentic voices, rather than just numbers and instructions, are important.

My research on risky drinking points to a strong desire for less data and more connection through narratives. And lastly, I’d say messages with some positivity.

This is tough in such troubling times, but rather than suggesting that young adults are selfish and problematic, rather than telling them off, noting the possibilities for what they can do, and praising the actions of those who do the right thing might be a more productive route.

Perpetuating negative stereotypes of a selfish generation is not going to help anyone.

This article was published by Lens.

Steven Roberts is an Associate Professor in the School of Social Sciences at Monash University. He has published widely on the ways in which social class and gender shape, influence and constrain young people’s experiences of and aspirations for education, employment, housing, consumption and the domestic sphere.