Listen without prejudice

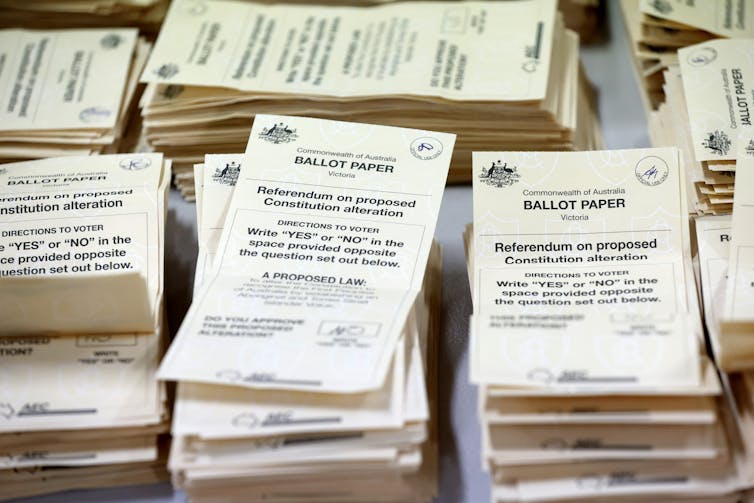

The outcome of the referendum has been chalked up to deepening political polarisation, Australian’s entrenched racial prejudice and the rise of populism.

In short, opposition to the Voice to Parliament has been characterised as a conservative populist backlash with racist undertones. In the wake of a 60/40 “no” vote majority, this message only serves to deepen the post-referendum divide.

However, new research indicates the story is a little more complex. Findings show it was fundamentally the esteem of authority, the desire for an ordered society, and perceptions of justice and fairness that dictated how people engaged with this emotionally charged political issue, and ultimately how they voted.

It is only by a greater understanding of people’s attitudes towards the referendum (even if we disagree with them) that Australians can move forward and have a more productive bipartisan conversation.

Supporting the status quo

We collected survey data from 253 people before and after the referendum. We wanted to get an idea of the way people’s worldviews would influence their vote and opinions about the outcome of the referendum.

In June 2023 (roughly 16 weeks before the vote) we asked about people’s attitudes towards authority, their opinion about social hierarchy, and their perceptions of justice in society. In October (immediately after the vote) we asked how people voted and whether they thought the outcome of the referendum would be good for Australia.

Our findings show people who voted “no” and who were pleased with the outcome were more willing to submit to authority. They also preferred a hierarchical society where the social status of different groups is maintained.

These attitudes were more important in predicting voting behaviour than a person’s age, gender, ethnicity, income, education, religion or even their political orientation.

Whereas social hierarchy beliefs are broad and refer to a person’s general view that it’s a “dog-eat-dog” world, racism relates more narrowly to discrimination against people based on their ethnicity. While there’s often a complicated relationship between preference for social hierarchy and racism, these findings counter the widespread claims that those who voted “no” were entirely racially motivated or were simply voting along political lines.

In understanding why some people voted “no”, these findings can promote a more open discussion.

For example, in the future when discussing profound and potentially momentous changes to the country (the current debate around nuclear energy, for example), it will be helpful to remember that people differ drastically in their willingness to follow along with authority.

Some will be quick to cotton on to messages from leaders and may act passionately (even aggressively) on these convictions. Others will be slower and more cautious in their support for ideas expressed by authority.

It will also be helpful to remember people have different ideas about how society should be structured. Some people will prefer a society with a clear pecking order, perhaps fearing the chaos of a disordered society. Others are less concerned with a clear structure in favour of things like social mobility.

Our findings show we shouldn’t reduce support for complex issues simply to one’s political orientation or demographic characteristics. We need to seek first to understand a person’s worldview and attitude towards societal change. Only then can we have a productive conversation about what is best for the country.

Perceived (in)justice

Populism is the idea that a small group of elite people are trying to force change on society. A populist backlash occurs when ordinary people rebel against the powerful minority and exert the popular will of the people. Voting down the referendum has been characterised in such terms.

Our data show people who voted “no” view society as a just place in which people are generally treated fairly. They didn’t accept the fundamental premise on which the referendum was sold: that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are, and have been, unjustly treated. This finding provides a helpful insight into the populist explanation for the referendum outcome.

At its heart, the populist narrative is a story of justice. The idea that the elite are pursuing their own agenda to the detriment of the people strikes us all as unjust.

But it is people who already see society as a just and fair place who are especially sensitive to this perceived injustice. These people can act out in sometimes extreme ways. Consider, for example, the January 6 storming of the US capitol.

By understanding the populist account in terms of justice, we can clearly see how the post-referendum divide in society has formed: those who voted “no” feel vindicated at having avoided an unjust change to society, while those who voted “yes” become wary of these people for their extreme and seemingly unwarranted reaction. Understanding not only the important role that justice plays in people’s lives, but also that people can have differing views of what justice is, is crucial to keep in mind.

In a world where political polarisation is increasing and where we are confronted with news (some real, some fake) that continually seems to deepen this divide, taking the time to understand the complexity of people’s worldviews and political opinions – even those you might disagree with – is more important than ever.

This article was published by The Conversation.

Jonathan Bartholomaeus is a Lecturer at the University of Adelaide where his interests include individual differences and social psychology.