Is technology slowing growth?

Even before COVID-19 hit, Australia was experiencing slow growth in GDP per capita and real wages.

There has been a distinctly lower rate of both economic and real wages growth since the financial crisis of 2008-09.

Advanced economies around the world have, to varying degrees, witnessed the same trends. If anything, Australia has done slightly better than other countries.

Why has growth slowed globally? That’s a real question.

What theory tells us

Basic economic theory tells us GDP per capita is driven by technological progress.

The so-called “neoclassical growth model”, developed in the 1950s by American Robert Solow and Australian Trevor Swan, saw technological progress as exogenous – attributable to an external cause. In a sense, the idea was that innovations just drop from the sky at some fixed rate.

In the early 1990s Philippe Aghion, Peter Howitt, and Paul Romer pioneered “endogenous growth theory” – that the causes are internal to the economic system. In particular their theory emphasised the development of ideas as crucial to technological progress.

Romer’s contribution was to highlight that producing ideas has large set-up costs but potentially low marginal costs of replication. Think pharmaceutical development, where R&D is very expensive but producing extra pills is cheap.

To make the development of new pharmaceuticals viable, therefore, some degree of monopoly power is required, so others who didn’t invest in developing them can’t simply copy the product. This suggests a crucial role for government policy, such as intellectual property rights and subsidies for basic research.

Developing pharmaceuticals is expensive, but making them is cheap.

Aghion and Howitt highlighted the role of “creative destruction”. Innovation can render old technologies obsolete.

Thus innovations come with externalities – costs or benefits for other parties.

Romer’s research emphasised the positive externalities – namely that ideas are non-rivalrous. For example, we can all use Pythagoras’s Theorem now it has been discovered.

The Aghion-Howitt framework emphasised the negative externalities. New ideas can render old ideas obsolete, thereby deterring innovation in the first place – why invest in R&D now if future R&D will render it all obsolete? But market power protects the rents earned by innovators.

This means, as Aghion and Howitt put it, the average growth rate “depends on the size and likelihood of innovations resulting from research and also on the degree of market power available to an innovator”.

What does this mean for wages?

Since wages are the returns to labour from economic value created economy-wide, technological progress is needed to drive real wage increases.

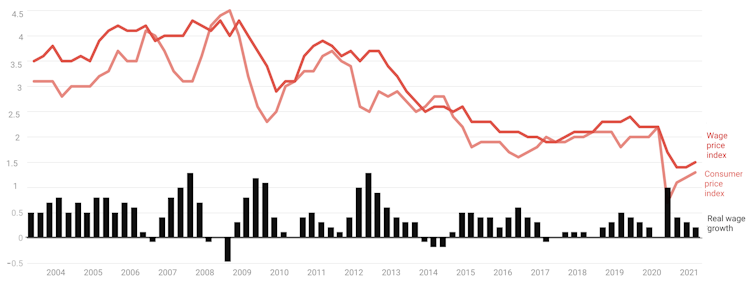

Real wage growth, per cent, 2003-2021

As Paul Krugman put it in 1994:

“Productivity isn’t everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.”

Or, to paraphrase legendary American political strategist James Carville: “It’s the productivity, stupid!”

Enter the Productivity Commission

Yesterday Australia’s Productivity Commission published its “second annual Productivity Insights” report.

In the foreword, chairperson Michael Brennan writes:

“The decade ending 2019-20 was the worst decade of growth in 60 years, and even if the last year of growth is excluded then this nine-year period still compares unfavourably to past decades. This mainly reflects a global productivity slowdown and the end of the mining investment boom, which has subdued investment and, through lower terms of trade, reduced the purchasing power of Australian incomes.”

That’s a pretty good summary of the concerning trends documented in the rest of the report.

Let’s take Brennan’s second observation first.

The end of the mining boom – you have to squint a little to ignore the current iron-ore price – has seen the Australian dollar drop from about parity with the US dollar to the range of 75-80 US cents. This makes buying goods largely denominated in US dollars – from mining equipment to point-of-sale terminals to computers – more expensive for Australian businesses and households.

It is a good reminder that the oft-mentioned claim a lower Australian dollar is good for exports, while true, ignores the fact we buy lots of capital equipment and consumption goods from overseas. A weaker dollar is bad news for buyers of those goods.

Now to Brennan’s first observation – that the productivity slowdown is a global phenomenon.

It has been clear for many years that we live in an age of “secular stagnation” – a term former US Treasury head Larry Summers popularised in 2013.

Simply put, there is a huge volume of global savings chasing fewer big investment opportunities.

Desperately seeking investment opportunities

Once capital was quite scarce. Now there are now massive sovereign wealth and retirement savings funds all looking to put their money to work. There are also many more billionaires with money to invest.

But where? Once it required huge amounts of capital to build the US railroads, or big oil and steel companies. Now some of the most valuable companies in the world have been created by brilliant students with a laptop in a dorm room.

An even more pessimistic view is that modern technologies are just not that revolutionary.

The leading proponent of this “techno-pessimism” is Robert Gordon of Northwestern University in Illinois. He argues in The Rise and Fall of American Growth (Princeton University Press, 2017) that the information technolgy revolution is a footnote compared to the prosaic inventions of the second industrial revolution, such as electricity, motor vehicles and aircraft.

There are, also, techno-optimists who point to the revolutionary potential of machine learning and other innovations.

Wherever one lands on this spectrum, it’s hard to get away from the idea that to drive living standards upward we need to harness technologies to relentlessly improve productivity.

The Productivity Commission is on the case. Now we just need Australia’s policy makers to embrace the type of economic reforms pulled off in the 1980s and 1990s, under governments of both political stripes.

This article was published by The Conversation.

Richard Holden is Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School. His research focuses on contract theory, law and economics, and political economy. He has also written papers on political districting, the boundary of the firm, incentives in organisations, mechanism design, and voting rules.