Fixing aged care

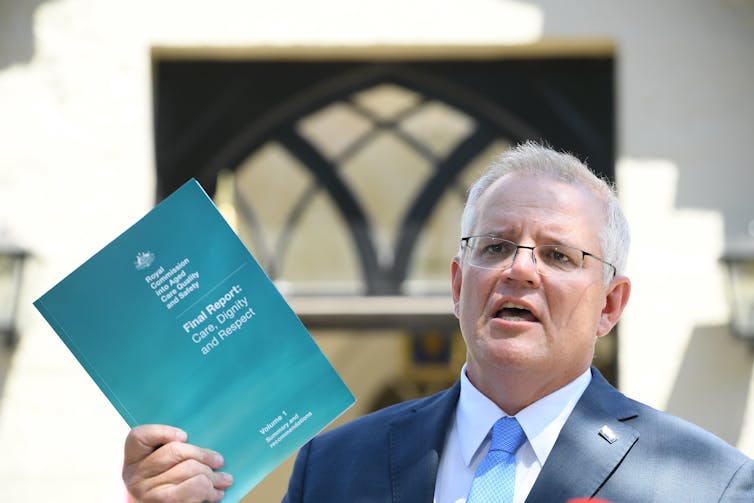

Australia’s aged-care system is in a state of a disaster. The aged care royal commission’s final report, released last month, is just the latest in a decades-long string of depressing reports and inquiries exposing horrific abuse, neglect, and systemic failures.

Aged care needs a complete overhaul. Piecemeal reform will not be enough. Although the two commissioners didn’t agree on everything, they did agree on the fundamental reforms needed to throw out the old paradigm of rationed care, which has left too many older Australians with inadequate care — or none at all.

In a new Grattan Institute report, we navigate the commissioners’ disagreements and identify four key criteria for transformational change.

Of course, fixing aged care won’t come cheap. We also set out some ideas as to how the government could secure the billions of additional dollars needed every year to fund a better aged-care system. In this regard, next month’s federal budget offers a crucial opportunity for the government to step up.

4 steps to forging a clear path to change

First, the government must develop a new Aged Care Act that enshrines the rights of older Australians and includes a universal entitlement to needs-based care. Reforms to create a single new integrated aged-care program that includes both home care and residential care categories would make care easier to access. This would also help ensure high-quality care for all older Australians who need it, without waiting times or co-payments for care.

Second, the government must introduce new independent governance arrangements, including independent pricing, independent quality standards, independent oversight, and regional governance structures.

This would help address poor regulation and failures in the current market-based system that have meant many older Australians haven’t been getting the level or quality of care they need. Better governance and enhanced transparency would help create a properly functioning aged-care system dedicated to providing high-quality care.

Third, the government must announce major reforms to the aged-care workforce. It must set and enforce minimum care hours per resident in residential aged care, set up a national registration system for all personal care workers, and mandate that all aged-care workers complete Certificate III training at a minimum.

Finally, the government must announce a massive boost in aged-care funding — and detail how they’re going to finance it.

Last month, the aged care royal commission released its final report. It’s time now for the government to act.

Coming up with the cash

People receiving care should contribute to their ordinary costs of living, such as accommodation. But the government should pay for their care costs, just as the government pays for patients’ costs in public hospitals (through Medicare).

This approach would provide universal insurance for people with high care needs, and would reduce the need for precautionary savings in older age, because people would not need to worry about how they are going to fund their possible care needs.

The royal commission identified a A$9.8 billion annual funding shortfall in aged care, and that figure will only increase as Australia’s population ages.

This funding gap could be financed through some combination of a Medicare-style levy on taxable income, changes to the pension assets test, reductions in tax breaks on superannuation, or other mechanisms.

The royal commission recommended a 1% aged-care levy on personal income tax, just like the Medicare levy, as a way to share costs across the community. This would raise about A$8 billion per year and cost the median taxpayer about A$610 per year.

Other tax measures targeted at wealthier older Australians would also help ensure equity in funding a better aged-care system.

The average household headed by someone aged 65-74 now has more than A$1.3 million in net assets. That figure has more than doubled in the past two decades. Counting more of the value of the family home in the pension assets test (a means test that determines your eligibility for the pension) above a certain threshold — such as A$500,000 — would make the pension fairer. It would also save the budget up to A$2 billion a year, which could be reallocated to aged care.

One of the critical areas to address is boosting staffing in aged care.

The government could also wind back excessively generous tax breaks for older Australians in superannuation, which result in only one in six people over 65 paying any income tax.

Superannuation earnings in retirement — currently untaxed for people with superannuation balances of less than A$1.6 million — should be taxed at 15%, the same as superannuation earnings before retirement. This would improve budget balances by about A$6 billion a year today, and much more in future.

Surveys consistently show Australians are willing to pay more tax to fix aged care.

Money has to be spent wisely

Pre-budget leaks suggest the government is prepared to invest additional billions in aged care, but the amount foreshadowed in a media report over the weekend — A$10 billion over a four-year period — is below what experts identify as necessary to fix the problems revealed by the royal commission.

Just as important, if the additional funding is not accompanied by system reform, then an opportunity will have been wasted, and the spending will be wasted on system inefficiencies and excess management fees rather than on improved services for consumers.

The time is now

Properly administered, extra funding could transform the aged-care system. It could clear the 100,000-long waiting list for adequate home care, provide higher-level care at home for longer, employ at least 70,000 more aged-care workers, lift the amount of care per resident, and ensure a qualified nurse is on site 24/7 in all residential care homes. But achieving these needed changes will require more than what appears to be on offer in the pre-budget leak.

The government must seize this moment. It must sharpen its pencil and take this historic opportunity where there is substantial public support for transformative change and fund the necessary reform fully. Next month’s budget should include policies — and funding — to create an aged-care system in which all Australians can take pride.

This article was written by Stephen Duckett, the Director of the Health Program at the Grattan Institute; and Anika Stobart, an

Associate at the same institution. It was published by The Conversation.

Stephen Duckett is the Director of the Health Program at the Grattan Institute. He has held top operational and policy leadership positions in health care in Australia and Canada, including serving as Secretary of what is now the Commonwealth Department of Health.