Digging below the surface of Australian farming

Like the Anzac soldier and bronzed surf lifesaver, the farmer holds a special place in the Australian imagination. Through hard work on a harsh and unforgiving continent, the farmer cultivated a nation. Or so the story goes.

Is this the whole story? Farming and agriculture were crucial to establishing the new nation, but they were also intimately involved in settler-colonial violence and dispossession of Indigenous Australians’ land and foodways.

The mythos of the farmer

In 1906, George Essex Evans celebrated the farmer in his poem, “The Men Upon the Land”. According to Evans, it is not the bankers or office workers who “shall make Australia great,” but:

the hearts that build the nation, are the men upon the land.

The agrarian nationalism of Evans’ poetry taps into a long history that regards the farmer as the backbone of society. In 1785, Thomas Jefferson, one of the founding fathers of America, famously described farmers as “the most valuable citizens”.

While factory workers and artisans could flee to another country if things got difficult, Jefferson said, the farmers:

…are tied to their country and wedded to its liberty and interests by the most lasting bonds.

As such, farmers put down literal and metaphorical roots in a place.

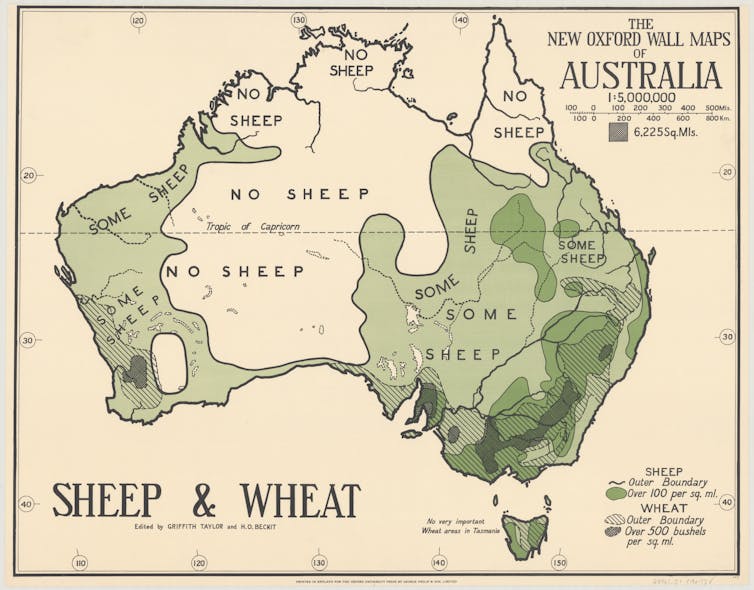

In the 1930s, these ideas of agrarian civic virtue formed the basis of the Country Party in Australia. Earle Page, 11th prime minister and leader of the Country Party (1921-1939), used the notion of “country-mindedness” to argue that Australia depended on farmers and graziers for its high standard of living. It was also the farmers who forged the core elements of the national character by taming the environment, making it productive, and creating a home.

Therefore, according to Page, the nation owes a special debt to the farmer.

The mythos of the Australian farmer who battled a harsh environment of drought, floods and fires continues today. Although over 85% of Australians live in urban centres, it is in the bush, writes historian Don Watson, where “the real Australians live”.

The existence of these “real Australians” – the bushman and the farmer – continues to authenticate and deepen urban-dwelling Australians’ claim to the continent. Note the way prime ministers from Bob Hawke to Malcolm Turnbull wear Akubra hats and R.M. Williams apparel and pose with tractors in a bid to appear “authentic”.

Violence of settling a new population

The celebration of the farmer for taming the continent and creating a homeland for white Australia, however, masks the role of agriculture in settler-colonial violence.

Agriculture played an important part in establishing settler-colonial societies such as Australia, as well as the United States, Canada and New Zealand. In contrast to exploitative colonialism, in which a nation takes all the mineral resources of a colony and then leaves, settler-colonialism seeks to establish a new and permanent society.

Agriculture allows a population to settle, reproduce and grow at the cost of Indigenous peoples.

As Patrick Wolfe, an anthropologist who studied settler-colonial societies, has observed, agriculture “progressively eats into Indigenous territory” for the reproduction of the settler population while simultaneously curtailing “the reproduction of Indigenous modes of production”.

This situation has forced Indigenous peoples to either enter the new economy of a colony, usually in the form of unfree labour, or raid farms for food, which Wolfe notes is “the classic pretext for colonial death-squads”.

In Australia, the expansion of agriculture led to many of the bloodiest massacres in the 19th century.

Declarations of the intent to murder were not kept quiet. In 1824, L. E. Threlkeld, an English missionary, records in his diary a public meeting in Bathurst where a man named William Cox, “one the largest holders of sheep in the colony”, declared:

…that the best thing that could be done, would be to shoot all the Blacks and manure the ground with their carcas[s]es, which was all the good they were fit for!

In May and September of that year, there were two separate massacres within 50km of Bathurst. At least 51 Wiradjuri men, women and children were murdered. It is unknown if Cox was involved, but from Threlkeld’s account, he had certainly made his views clear.

Agricultural and evolutionary progress

Agriculture not only instigated violent clashes, but was also used as an evolutionary marker. The “stadial theory” of societal evolution, associated with the Scottish Enlightenment in the 18th Century and influential at the time of colonisation, held that there are four stages of civilisation: hunter and gather, pastoral and herding, settled agriculture and commercial exchange.

On this basis, Aboriginal Australians were regarded as the lowest stage of societal evolution, a stage where there were no property rights and therefore no basis for claims to territory.

As early as Lachlan Macquarie’s tenure as governor of NSW in the 1810s, efforts were made to forcibly transform local Indigenous populations into settled farmers.

In 1840, the London-based Imperial Land Commissioners advised NSW Governor George Gipps that:

…reserves of Land should be made for [Aboriginal peoples’] use and benefit in order that the best means should be taken for enabling them to pass from the hunting to the agricultural and pastoral life.

By the 1860s, farming and gardening were key activities of the “civilising” process of the protectorates and missions. It was believed that cultivation and improvement of the soil would correspond to a cultivation and improvement of the self.

Yet, in this process of “improvement”, traditional lands were stolen and intricate systems of knowledge disrupted.

These are not the stories we tend to tell about farming in Australia. Few books on the history of agriculture in Australia mention the violence, dispossession and evolutionary ideas that contributed to the destruction of Indigenous foodways.

Instead, we focus on the resilience and the triumph of the farmer battling the elements and creating a new homeland. According to environmental historian, Cameron Muir, this myth is:

…founded on a perception of the Australian environment as hostile and useless, and hence why the moral character of those who battled the land and made it grow European commodity plants was revered.

But was the environment hostile to human flourishing?

The belief that Australia was inhospitable ignores the fact that Indigenous peoples had lived on the continent for more than 60,000 years.

Tragically, over the past 230 years, Indigenous foodways have progressively been decimated, and today Indigenous Australians suffer disproportionately from food insecurity and diet-related diseases.

Thus, the myth of the battling farmer not only celebrates but silences historical wrongs and their present-day effects.

A way forward?

The recent recognition of the work of Bruce Pascoe and others has challenged the centuries-old “accepted view” of Indigenous peoples in Australia as:

simply wandering from plant to plant, kangaroo to kangaroo in hapless opportunism.

Pascoe highlights the intricacy and sophistication of Indigenous foodways in cultivating, harvesting and processing foods.

Drawing on the work of Pascoe, Charles Massy, a fifth-generation sheep farmer in NSW and agriculture reform advocate, has tried to promote his approach to “regenerative agriculture” within the context of the history of Australian agriculture – a history he considers environmentally and socially destructive.

He acknowledges the importance of recognising the past and continuing connection of Indigenous peoples to the land and contends that to:

…manage, nurture and regenerate country, then we need to fathom where it came from … what it is made of, how it works and functions, how it was managed before us.

While we can’t change past wrongs, we can start re-thinking the environmental, social and political implications of the way we produce our food on this continent.

Restoring the land and environment is important, but we also need to address the role of farming in dispossession and violence. This is not only about remembering, but moving forward in a way that avoids repeating the past and may open up ways of restoring Indigenous foodways and listening to the voices of those who have suffered and resisted settler-colonialism.

This article was published by The Conversation.

Christopher Mayes is a Research Fellow in the Alfred Deakin Institute at Deakin University. His research interests include the sociology of health and food, bioethics, and social and political theory.