China’s shadow falls across the Pacific

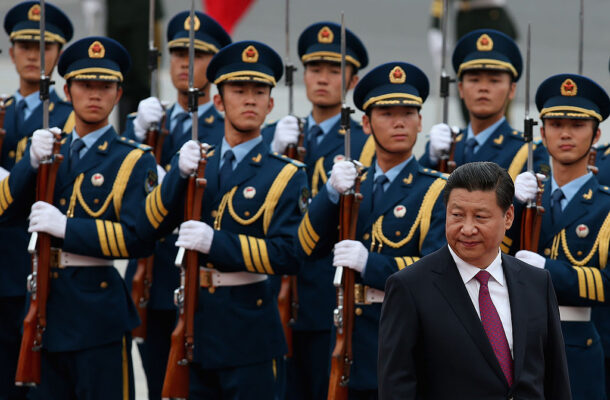

Echoing Russian President Vladimir Putin’s description of his war in Ukraine, China’s Xi Jinping has released a directive that licenses his armed forces to conduct ‘special military operations’.

This involves the People’s Liberation Army using force outside circumstances that other nations would consider as war. The guidance is consistent with Beijing’s recent coastguard law, which allows that well-armed organisation to use lethal force wherever China claims jurisdiction (as it does in the South China Sea despite its claims being comprehensively rejected under international law). It seems likely to apply to the Taiwan Strait if Xi persists in attempting to assert that the strait is Chinese waters, not a key international waterway.

Xi’s new directive has clear implications for the people of Solomon Islands, as it tells the PLA to use force where required to protect Chinese nationals and Chinese projects and investments. Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare’s deal with Beijing talks about this too, so what Xi is now doing with his military will be applied in the ‘security assistance’ that China’s authoritarian forces provide in and around the Solomons. Like with the Sogavare–Beijing pact, Xi has not released the text of his directive, just had it reported in state media.

Chinese Defence Minister Wei Fenghe, who said at last weekend’s Shangri La Dialogue that he wanted a new positive relationship with his Australian counterpart, Richard Marles, will implement Xi’s direction. The result will be in an even more aggressive PLA in the South China Sea, around Taiwan and Japan, and on the India–China border.

What does all this mean for the prospects of a sustained positive ‘reset’ in the bilateral relationship between Australia and China? All bad things.

It looks very likely that the reset has been gazumped by a more outwardly focused, increasingly aggressive PLA that seeks to define its use of force as ‘not war’.

Definitions that deny reality may work in the land of the Chinese Communist Party. But as Putin is experiencing with the international reaction to his ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine, just calling something what it is not doesn’t prove convincing anywhere in which there’s freedom of expression and media that’s not closely supervised and censored.

The Marles–Wei meeting was a positive development because it’s the only ministerial-level contact between the two countries since China began its diplomatic freeze and then its continuing campaign of economic coercion against Australia in 2020.

It’s also a positive that the meeting happened without Australia needing to show major policy change beforehand. China had demanded that Australia change its policy decisions and directions to resume dialogue—notably in Beijing’s list of ‘14 grievances’.

So, what does Beijing want as the price for resuming dialogue?

Beijing may want the warmer tone and senior meetings to make it harder for Australia to oppose China’s growing military presence in the South Pacific, and harder for Marles to end the Chinese port operator’s lease over the strategic Port of Darwin. There’s leverage there because that would give Beijing a pretext to claim Australia had ended the ‘thaw’.

Wei’s continued line in speeches and dialogues is to assert that China’s approach is one of peaceful cooperation and win–win outcomes, and that anyone noticing anything aggressive or negative in Chinese military or broader government behaviour is smearing China, hurting the feelings of the Chinese people, and adopting a destructive Cold War mindset—usually by being a slave to the US.

Wei’s Shangri-La speech takes this position. That creates a credibility gap for him in dialogue with counterparts like Marles because the PLA he directs is not behaving in any way that could be characterised as peaceful cooperation in pursuit of win–win outcomes.

Instead, the PLA’s aggression in international airspace and waterways is growing, to the extent that mid-air collisions and crashes and on-water incidents are becoming likely as China tries to enforce rights it just doesn’t have.

A broad warming of the Australia–China relationship cannot occur while Beijing persists with unilateral economic coercion across several sectors of our economy; while the PLA behaves increasingly dangerously and aggressively in the South China Sea, around Taiwan and near Japan (all places where the Australian military operates along with partners); or while Beijing accelerates its direct military presence in Solomon Islands and potentially in other parts of the South Pacific.

Marles clearly understands this, using his speech at Shangri La to say: ‘What is important is that the exercise of Chinese power exhibits the characteristics necessary for our shared prosperity and security. Respect for agreed rules and norms. Where trade and investment flow based on agreed rules and binding treaty commitments. And where disputes among states are resolved via dialogue, and in accordance with international law.’

So, the new Australian government’s tone may not be the same as its predecessor’s, but the structural policy directions—on security risks in foreign investment (notably from Chinese entities) and the priority on countering foreign interference in Australian politics, countering traditional and cyber espionage, and working with allies and partners to confront the now overt strategic partnership between Russia and China—all mean that the foundations and differences between Australia and China persist. In fact, the differences are growing as Xi leads China down the path he has chosen.

Given Xi’s latest policy directions to the PLA and the growing gap between General Wei’s words and the PLA’s actions even before this, we should expect resumed government-to-government dialogue to be broadly disappointing to Australia.

That’s because Beijing wants us to compromise but intends to make no significant compromises itself. (This is not unusual or particular to the China–Australia relationship. Wei made it clear that for US–China relations to improve, for example, the US had to make positive moves to reset the relationship. That’s a line many of us hear in our dealings with Beijing, and one Beijing’s foreign ministry has already returned to since the Marles–Wei meeting.)

We should expect Beijing to accelerate its plan to have a direct military presence in the South Pacific and to conduct the newly minted ‘special military operations’ Xi envisions there. This will be a sufficiently grave and adverse development for Australia that the already strong public opinion that assesses China under Xi to be a threat to Australia’s security will harden. And in a democracy, that drives policy.

A collision in the South China Sea, on the water or in the air, would have a similar effect—and it would reverberate well beyond the Australia–China bilateral relationship.

This article was published by The Strategist.

With all this, the Albanese government is likely to continue a more positive, more engaged approach to other key partners in our region. That’s good news for bilateral relationships like the growing ones with Japan, South Korea, India and Indonesia, as well as for minilaterals like the Quad and the Australia–US–Japan trilateral, all underpinned by the military advantages Australia, the US and the UK will bring to the region through AUKUS.

These partnerships and the military power and advantages that come from them seem even more needed considering Xi’s latest move with the PLA.

Michael Shoebridge is the Director of the Defence and Strategy Program at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. He previously served in the Department of Defence and the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet.