China verses the world

Since coming to power in 2012, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary and State President Xi Jinping has been impatient to bring about a rejuvenation of the Chinese nation (zhonghua dafuxing).

His signature slogan — the China Dream — encapsulates the ambition to restore China to its rightful place among the world’s great powers by becoming a rich country with a strong army (fuguo qiangjun). The goal is that by 2049 (the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China and the CCP’s 100th year in power), China will have achieved ‘fully developed’ (fada) nation status.

This centennial goal, according to Kerry Brown, author of this week’s lead essay on the East Asia Forum, ‘is intended to be a symbolic moment where the Communists can say that, for the first time in modern history, China can stand secure, strong and respected as a major power once more. [The rise of China by 2049] is intended to be the final resolution to the “century of humiliation narrative” where China was colonised and divided by outsiders’.

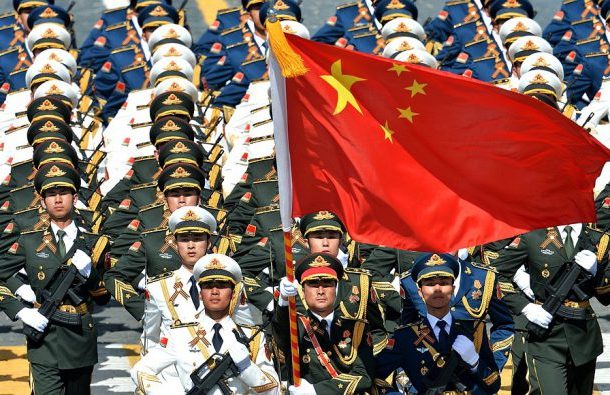

Although 2049 is three decades away, President Xi is wasting no time in seeking to strengthen China economically and militarily. He has set ambitious economic targets such as ‘Made in China 2025’ — a strategic plan to turn China into an advanced manufacturing powerhouse— and he has invested heavily in the modernisation of the People’s Liberation Army.

Jettisoning paramount leader Deng Xiaoping’s ‘hide your strength and bide your time’ approach to foreign policy, which was judiciously followed by Deng’s successors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, Xi Jinping has shown inclination to outwardly brandish China’s emerging tech prowess and military might.

Under his rule, China has adopted a confrontational stance in the South China Sea, announced eye-wateringly ambitious plans to build new infrastructure links between Asia and Europe and promised to be the first country to soft land a probe on the far side of the moon.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Xi’s muscle flexing has raised anxieties and hackles around the world, where major capitals are being forced to contend with the realities of Chinese power much sooner than they might have expected. And the blowback has begun.

Although Chinese officials proclaim that Made in China 2025 is just a plan to reduce reliance on foreign technology and to avoid the ‘middle-income trap’ that purportedly prevents low-tech industrial economies from advancing to high-income status, the Trump administration is treating the plan as a synonym for unfair trade practices, including intellectual property theft and forced technology transfers. Trump has imposed hard-hitting tariffs in what could become the first salvos in an all-out trade war.

Elsewhere Chinese investments are being subjected to greater scrutiny, particularly infrastructure loans that are based on debt-for-equity contracts. Such contracts are increasingly seen as a ploy for China’s eventual takeover of critical infrastructure that can be used to control trade and project military power.

The Chinese state’s domination of the investing entities, either through direct ownership or indirect controls, is raising further alarms about the intent of Beijing’s economic statecraft. The world is now being forced to ask: is China an aggressive mercantilist power or is it a peaceful, pro-free trade global citizen?

The CCP appears to realise the problem. Writing about Xi Jinping’s recent speech to the Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs on the subject of ‘major-country diplomacy with Chinese characteristics’, Kerry Brown observes a tension between the leadership’s desire that China be seen as globally important and powerful (which pays a domestic political dividend) and the need not be seen as a threat, especially by the United States.

Xi’s prominent speech — which was attended by the full Politburo Standing Committee — highlights Xi’s concern about getting the messaging right. Referring to a Xinhua report of the speech, Brown notes an effort to link the aspirations of the China Dream to the notion of ‘promoting human progress and making contributions to the building of a community with a shared future for humanity’.

The intended message is clear: China’s rejuvenation is good for China and good for the world. But Brown pinpoints a tension in the speech’s rhetoric ‘between the nationalistic tone invoked domestically and the attempt to craft a friendlier and appealing external language that the rest of the world can embrace’.

This is the balancing act that China’s ‘major-country diplomacy’ must achieve. The question, Brown asks, is whether China ‘will be pulled decisively in one particular direction’. Brown’s assessment is that, for now at least, Xi wants the balance to continue.

Xi’s ability to wrangle these competing domestic and international forces is an idea that is challenged by William Overholt who reckons that we misunderstand altogether what’s going on in China today. He argues that anyone who thinks Xi Jinping is ‘an all-powerful president for life running an economy inexorably destined for rapid growth’ has got it wrong.

The narrative about China that has come to dominate in the United States and that has captured high ground in countries like Australia and elsewhere suggests that the Chinese state is led by the most and authoritarian powerful leader since Mao Zedong. China has somehow escaped the pressures for political change that transformed earlier Asian miracle economies at similar levels of development.

It has consolidated a particularly repressive market Leninism, which is destined to grow rapidly for the indefinite future. And its centralised economic control and ambitious industrial policies are so efficient that they constitute an unrestrained threat to the West.

This narrative, Overholt suggests, flies in the face of facts and the reality in China. He urges more confidence in the free enterprise system and more perspective on China’s political dilemma. Engagement with China has not failed, he says: it has created the anticipated social and political pluralism that it set in train. In this conception, self-destructive repression will be at the cost of interrupting China’s rise. China could democratise, or it could find a new way to channel the tide of pluralism.

Perhaps he has a point: that critics of the engagement with China understand neither the time required for change in China’s vast society nor the truth beneath Xi’s adulatory headlines.

Read more on China’s rise at the East Asia Forum.

Dr Shiro Armstrong is a Research Fellow at the Crawford School of Economics and Government, Australian National University, Executive Director of the East Asian Bureau of Economic Research and Co-Editor and Co-Founder of both the East Asia Forum and East Asia Forum Quarterly.