Back from the bush

First person accounts of a bushranger’s life are rare: there are very few bushranger memoirs or autobiographies.

A couple of exceptions appeared in the 1870s, both of which presented themselves as adventure narratives.

Martin Cash’s autobiography is a breathless, rollicking account of his various escapades.

Martin Cash – a ‘life in the woods’

Born in County Wexford, Ireland, Martin Cash was transported to Warrane/Sydney (he had tried to shoot a romantic rival) in early 1828, on the convict ship Marquis of Huntly.

Wanted for cattle stealing later on, Cash fled New South Wales for Van Dieman’s Land; the first thing that caught his attention when he arrived there was a coffin containing the body of a hanged bushranger.

His autobiography, The Adventures of Martin Cash (1870), is a breathless, rollicking account of his various escapades on the island with “two desperate men” from New South Wales, Lawrence Kavanagh and George Jones. The gang roams through the forests (“A life in the woods for me!”), raiding property after property, with police and soldiers in constant pursuit.

Captured at last and placed on a ship destined for Norfolk Island, someone hands him a sheet of paper with a ballad on it that celebrates Cash’s Irishness and his courage:

“He’s the bravest man that you could choose from Sydney men or Cockatoos,

And a gallant son of Erin, where the sprig of Shamrock grows.”

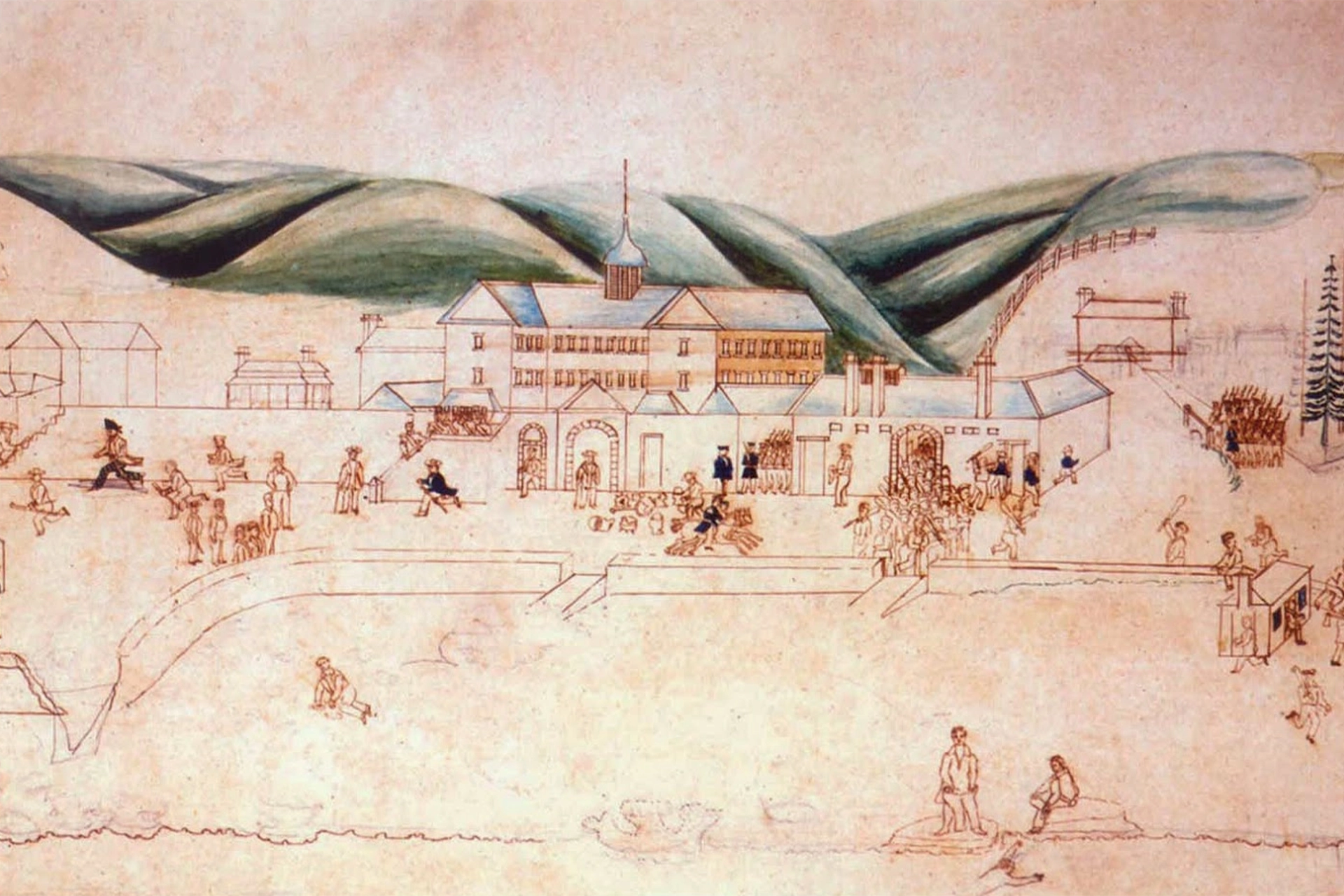

Marcus Clarke had drawn on Cash’s experiences at Norfolk Island in the mid-1840s, under the commandant Joseph Childs, for the last part of For the Term of His Natural Life.

William Westwood – an ‘inoffensive man’

At one point in his Adventures, Cash describes a mutiny and some killings by convicts, led by the ex-bushranger William Westwood, an otherwise “quiet inoffensive man” who had been “flogged, goaded, and tantalised till he was reduced to a lunatic and a savage”.

The penal colony’s religious instructor, Thomas Rogers – the model for the Rev. Mr North in His Natural Life – spent time with Westwood in his condemned cell and encouraged him to tell his life story.

Westwood was hanged in October 1846. For some reason, Rogers didn’t publish the notes he had taken until much later on, serialising Westwood’s narrative (under the pseudonym ‘Peutetre’) in four weekly issues of the Australasian in February 1879.

As it happens, it was around the time that Ned Kelly and his gang were raiding Jerilderie in the Riverina region of New South Wales, just north of the Victorian border.

William Westwood led the “Cooking Pot Uprising” on Norfolk Island in 1846.

For Rogers, Westwood’s narrative reveals “the incidents and motives of a bushranger’s life from a point of view from which it is seldom seen”, offering an “unadorned and straightforward tale of audacious bushranger adventure and privation, in which a young outlaw relates in his own way the incidents of his brigand career.”

Westwood was transported to Warrane/Sydney Cove on the Mangles in 1837. He soon absconded and was involved in numerous bail ups on the road.

His robberies were audacious: in one, he holds up a wealthy settler’s house, where a female servant wants to run off with him (“a faithful companion was she”); in another, he robs one of the magistrates who had sentenced him.

At Port Arthur later on, he is flogged and put in solitary confinement. When he absconds again, he is given a ten-year sentence on Norfolk Island: this is where his autobiography comes to an end.

Ned Kelly – he who ‘must be obeyed’

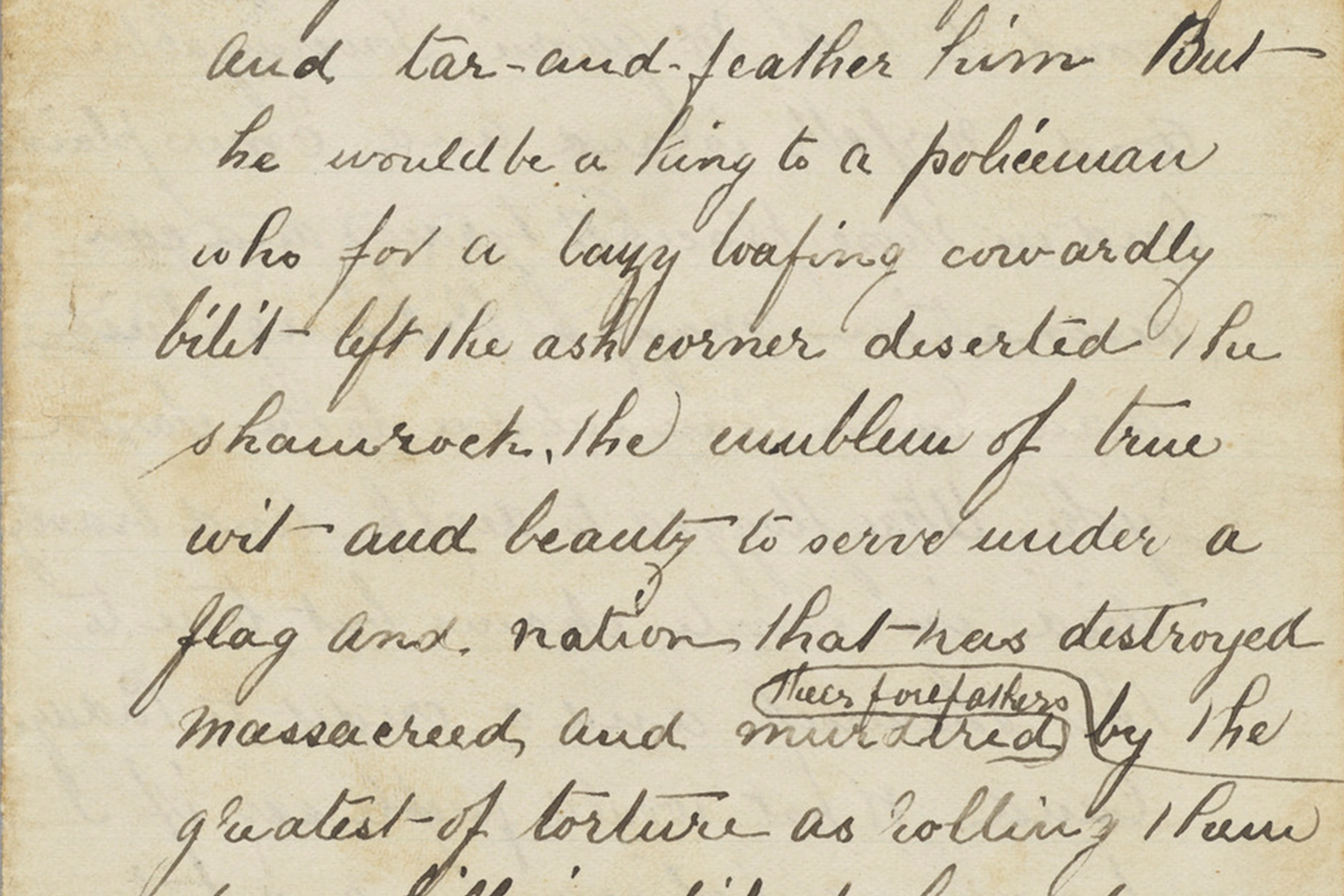

Ned Kelly’s Jerilderie Letter is the third bushranger’s autobiography worth noting here, the best-known example of a bushranger’s unmediated voice recounting actual experiences.

Kelly had already completed his manuscript by the time his gang got to Jerilderie, and he tried to get it published in the town’s newspaper; but in fact, it wasn’t published in its entirety until 1930.

The Letter is a remarkable document, a fascinating account of Kelly’s various battles with the police that escalates into a ranting diatribe against colonial authorities and the colonial state.

It has often been discussed in detail, but we can look at a passage here to appreciate the rhetorical force of Kelly’s mode of expression, its vivid condemnation of the brutalities of the penal system, and the way he radicalises himself by insisting on his unbroken connection to Ireland – unlike the Irish colonial policeman in this opening line:

“A policeman who for a lazy loafing cowardly bilit [billet, at a police station] left the ash corner [i.e. the fireplace or hearth at home] deserted the shamrock, the emblem of true wit and beauty to serve under a flag and nation that has destroyed massacred and murdered their forefathers by the greatest of torture as rolling them down hill in spiked barrels pulling their toe and finger nails and on the wheel.”

The language in this passage (and all through the Letter) is in some respects closer to poetry than to the ‘unadorned’ prose we might usually expect from a bushranger’s autobiography.

The historian Mark McKenna has dismissed the Letter as “aggressive” and “belligerent”, a “shallow form of republicanism” without any real political purpose.

Ned Kelly’s Jerilderie Letter is closer to poetry than prose.

Certainly, it is not quite the declaration of civil war we saw sixty years earlier in Michael Howe’s letter written in blood to Lieutenant-Governor Thomas Davey.

But it works in a similar way, escalating its rhetoric in a last-gasp series of threats against the police who Kelly hated so intensely. Those who support them, he suggests, should give their money instead to “the poor of Greta district”.

The powerful end of the Jerilderie Letter sees Kelly transformed from a bushranger wanted by the law to someone who imagines he is the law: this is his derangement. A lone voice in the wilderness at this point, he nevertheless promises retribution to the colony’s authorities.

By the end of the Letter, it is as if he has become a force of nature:

“Do not attempt to reside in Victoria but as short a time as possible after reading this notice, neglect this and abide by the consequence which shall be worse than rust in wheat in Victoria or the drought of a dry season to the grasshoppers in New South Wales. I do not wish to give the order full force without giving timely warning but I am a Widow’s Son, outlawed and my orders must be obeyed.”

This edited extract from Colonial Adventure: Australian narratives of colonial discovery, written byProfessor Ken Gelder of the University of Melbourne and Rachael Weaver, was published by Pursuit.

Open Forum is a policy discussion website produced by Global Access Partners – Australia’s Institute for Active Policy. We welcome contributions and invite you to submit a blog to the editor and follow us on Facebook, Linkedin and Mastadon.