A golden opportunity to repurpose old mines

There are about 50,000 abandoned mine sites across Australia, lying among communities and giving rise to myriad social, health and environmental concerns. Approximately 19,000 of these are in Victoria.

Most of these mines date from Australia’s prosperous gold-mining era, yet their impacts are still felt by communities today. Dust pollution and contamination of natural waterways are among the serious issues faced by surrounding communities.

However, there are opportunities for some areas to be revitalised while bringing value back to the mine.

Recent legislation in Australia has focused on the issue of progressive rehabilitation during an existing mine’s life cycle. However, it remains unclear what purpose these mines should serve at the end of their lives. More specifically, what can we do with the thousands of abandoned mines and quarries littered across the country?

Opportunities for value after closure

Australia’s abandoned mines don’t have to be a liability; instead, they can become an asset if properly managed. In fact, our national policy for old mines recommends “valuing abandoned mines”.

This could include further mineral extraction via secondary mining such as reprocessing tailings; industrial archaeological heritage conservation and tourism; unique habitats for biodiversity enhancement; collaborative research into innovative solutions to contamination problems, which could guide the broader industry; and Indigenous and other employment and training opportunities for regional Australia.

Across the world, abandoned mines have been rehabilitated and repurposed to support local communities.

Our research team has investigated the potential of rehabilitating mines for alternative end uses, including storage for water supply, flood retention, and as municipal waste containment facilities.

Victoria is in prime position to lead the rest of Australia in mines rehabilitation that can serve communities well into the future.

Rehabilitation for flood retention

As populations continue to rise, increasing urbanisation alters the natural hydrologic cycle, and we face more extreme and heavy rainfall events. Many communities in rural areas and along the urban fringes will face increasing flood risk.

If an abandoned mine is nearby, water can potentially be redirected to it, thereby providing storage and attenuation of flood waters, reducing the vulnerability of the catchment and affected regions downstream. Retention basins provide additional benefits, such as increasing biodiversity conservation through the restoration and provision of natural areas.

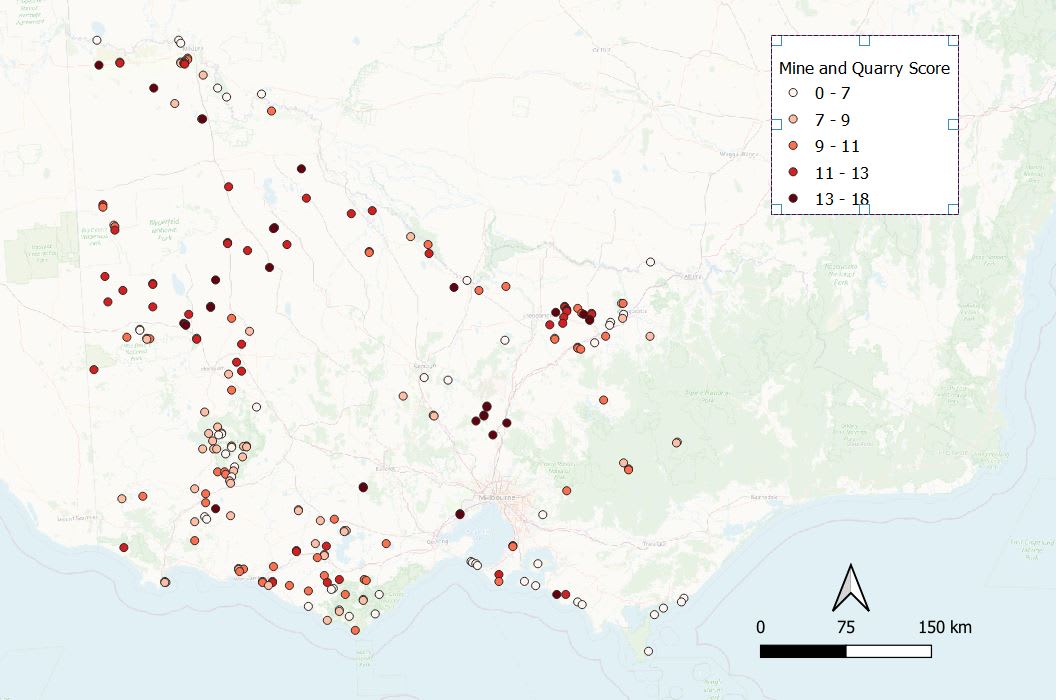

Our analysis highlighted two clusters of abandoned mines most suitable for rehabilitation. One is north of Melbourne’s urban fringe in Kilmore, and another is in northwestern Victoria.

This is largely due to higher levels of population growth expected in Kilmore, and greater soil suitability in northwestern Victoria. (Our analysis defines greater soil suitability as areas with sandy soils that are able to more swiftly absorb water.)

Rehabilitation for water supply storage

Another use for abandoned mines is water supply storage.

Such an initiative is underway in Atlanta, in the US, where an abandoned granite quarry is being rehabilitated for water storage. The quarry receives water from a nearby water treatment plant about 8km away, and will extend Atlanta’s water supply from five days to 30 days. Additionally, the project creates significant recreational space for the surrounding area, with the quarry at the centre.

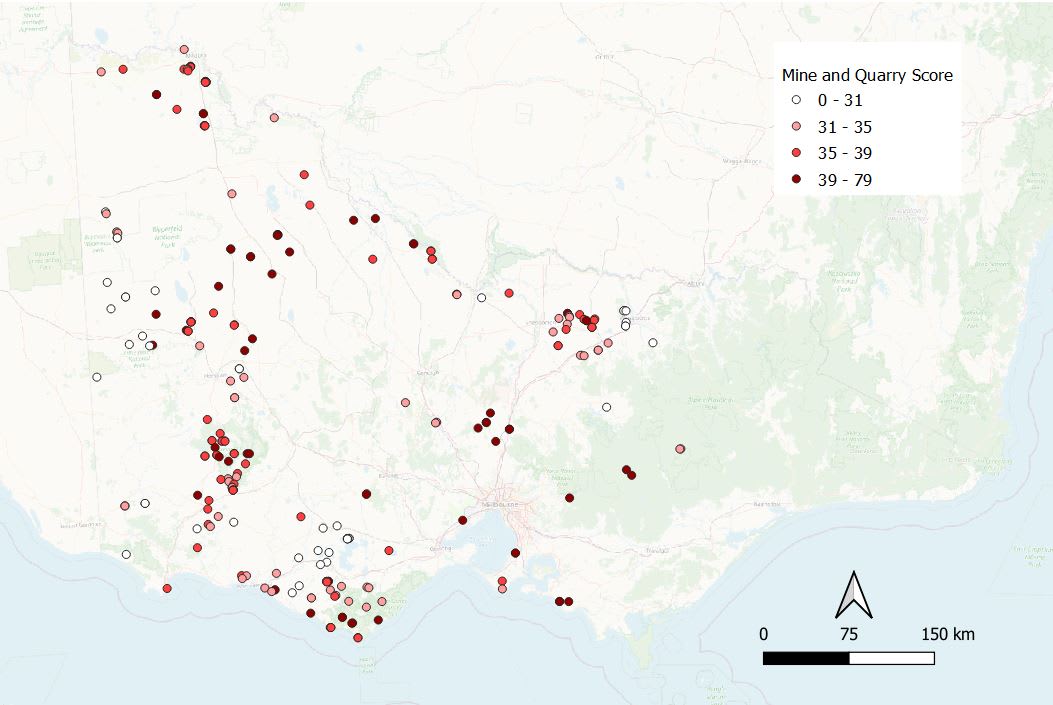

Closer to home, even though the most desirable mine for water supply storage is located south west of Kilmore, further investigation showed that it was too small to deliver any significant benefit to the water supply, highlighting the importance of also considering site characteristics.

The second-most desirable mine is southeast of Mount Eliza, in the Moorooduc nature conservation reserve, and has a potential maximum capacity of 665 megalitres.

The quarry is 9.7km away from the Mount Martha Water Recycling Plant. This plant produces Class A recycled water, and could potentially provide a stable supply to the proposed water supply storage. The rehabilitation of this quarry would also improve the damaged landform.

Rehabilitation into waste management

Victoria’s growing population also increases demand for waste management facilities. Urban sprawl places challenging restrictions on the placement of municipal landfills.

Some abandoned quarries and mines could present viable opportunities for additional waste disposal sites.

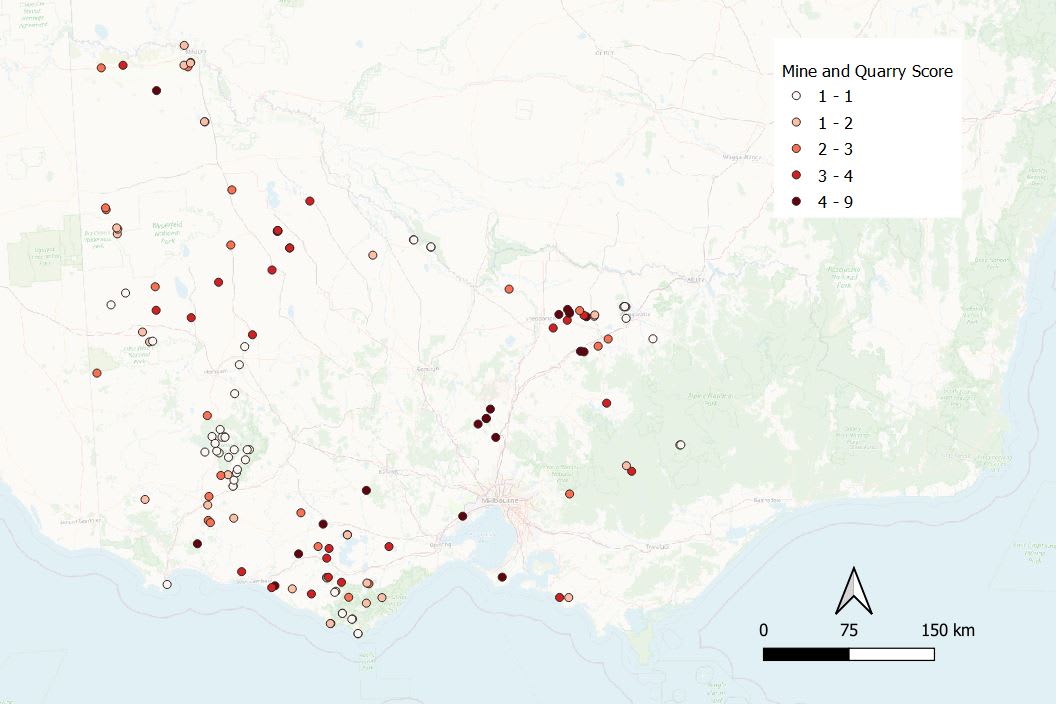

The Environment Protection Authority of Victoria’s publication of the “Siting, design, operation and rehabilitation of landfills” sets out a best-practice plan for the entire landfill life cycle.

We examined Victoria’s abandoned mines and quarries using this framework to find suitable sites that meet the guidelines’ minimum safety requirements. Some of these included a minimum of 100 metres from all surface water, 500 metres from any building or structure, and two metres’ separation from the groundwater table.

Our analysis showed a particularly high-ranking set of sites in the Kilmore region. These could be strong candidates for future landfill sites to service Greater Melbourne. As shown in the water supply storage case, additional site-specific analysis would be required to ensure the long-term suitability and safety for landfill facilities.

Mine-site rehabilitation is a growing challenge that all states and territories will need to face. Our work has demonstrated how opportunities can be ranked and compared in order for better decisions to be made.

However, more research is needed to better understand how we can transform these sites into multi-functional spaces that can deliver a greater suite of ecosystem services for the benefit of local communities and the environment.

Suitable approaches would also lead to improvements in the current rehabilitation regulatory framework, greatly reduce the impacts of mining operations, and provide further clarity for future rehabilitation requirements and end-use planning.

Dr Yellishetty’s research team on the project includes Melissa Truong, Han Chung Chia, Thomas Richards, Dr Stuart Walsh of Department of Civil Engineering, Monash University, and Dr Peter Bach, Research Scientist, Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science & Technology (Eawag / ETH). This article was published by Lens.

Mohan Yellishetty is an Associate Professor of Civil Engineering at Monash University. His research and academic experience includes working at CSIRO, Yale University in the USA and IIT Bombay and India.