One of the most haunting poems of the 20th century, T.S. Eliot’s The Hollow Men (1925), concludes:

“This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.”

In 1958, on his 70th birthday, Eliot was asked whether he would consider writing these lines, probably his most quoted, again. His answer was both noteworthy and categorical.

He admitted he would not. He said that “while the association of the H-bomb is irrelevant to it, it would today come to everyone’s mind”. (And he was “not sure that the world will end with either”.)

Indeed, Nevil Shute’s classic novel of nuclear annihilation, On the Beach, published in June 1957, used Eliot’s famous lines as an epigraph. And the nuclear threat is still very much at the top of our collective mind.

The Sydney Theatre Company is staging the very first stage adaptation of Shute’s novel. And Oppenheimer, one of 2023’s two most-hyped films, tells the story of the man referred to as “the father of the atomic bomb”.

‘Australia’s most important novel’

Journalist Gideon Haigh calls On the Beach “arguably Australia’s most important novel – important in the sense of confronting a mass international audience with the defining issue of the age”.

British-born Shute emigrated in 1950 to Australia, where he lived outside Melbourne. As well as writing novels, he worked as an aeronautical engineer.

The title of On the Beach – which started life as a four-part story called The Last Days on Earth – ostensibly referred to a Royal Navy expression for reassignment. (Shute spent time in the Royal Naval Reserve during the second world war.) However, as readers of Eliot’s poetry will know, the phrase also appears late in The Hollow Men:

“In this last of meeting places

We grope together

And avoid speech

Gathered on this beach of the tumid river.”

As in Eliot’s poem, the characters that cluster together in the pages of Shute’s novel, set in and around Melbourne between 1962 and 1963, tend on occasion to avoid speech.

This comes to the fore in the following passage, which focuses on a dinner party hosted by Lieutenant Commander Peter Holmes of the Royal Australian Navy. The atmosphere is both claustrophobic and delirious:

“For three hours they danced and drank together, sedulously avoiding any serious topic of conversation. In the warm night the room grew hotter and hotter, coats and ties were jettisoned at an early stage, and the gramophone went on working through an enormous pile of records, half of which Peter had borrowed for the evening. In spite of the wide-open windows behind the fly wire, the room grew full of cigarette smoke.”

The reason why the guests at Peter’s party are so keen to avoid serious talk is both simple and depressing. They are trying very hard to forget that they are all going to be dead from radiation poisoning in a matter of months.

Shute brings the reader up to speed after the dinner party wraps up. A massive nuclear war has devastated the entire northern hemisphere, wiping out all forms of life there. And the radioactive fallout generated during the conflict is now creeping – slowly but surely – into the southern hemisphere.

Shute makes it clear there is absolutely nothing anyone can do about this. In tonally dispassionate prose, he reveals that vast swathes of Australia have already been rendered uninhabitable due to radiation poisoning. The only thing the characters who remain can do is wait.

As Moira Davidson says to the American submarine captain, Dwight Towers: “It’s like waiting to be hung.” Hence the desperate need for moments of temporary respite and distraction.

Different characters deal with the situation in different ways. Those who still have jobs go to work. Those who don’t, stay at home or go shopping. Some, like Moira, take to drink and rail uselessly against the unfairness of it all:

‘I won’t take it,’ she said vehemently. ‘It’s not fair. No one in the Southern Hemisphere ever dropped a bomb, a hydrogen bomb or a cobalt bomb or any other sort of bomb. We had nothing to do with it. Why should we have to die because other countries nine or ten thousand miles away from us wanted to have a war? It’s so bloody unfair.’

Moira’s anger eventually gives way to something approaching resignation. “A tear trickled down beside her nose and she wiped it away irritably; self-pity was a stupid thing, or was it the brandy?” She comes to accept this is “the end of it, the very, very end.”

Moments after this, Moira, who is already gravely ill with radiation poisoning, ends her life. She takes a couple of suicide tablets, puts them in her mouth, and washes them down “with a mouthful of brandy, sitting behind the wheel of her big car”.

This is the way Shute’s novel of nuclear extinction ends: not with a bang but with a whimper. Released at the height of the Cold War, On the Beach struck a chord with millions of concerned readers.

Usefully entertaining

By the September of 1957, Shute’s novel – which sold over 100,000 copies within six weeks of initial publication – had been serialised by dozens of American newspapers. A copy had found its way to the desk of John F. Kennedy, the next president of the United States. And Hollywood was about to call.

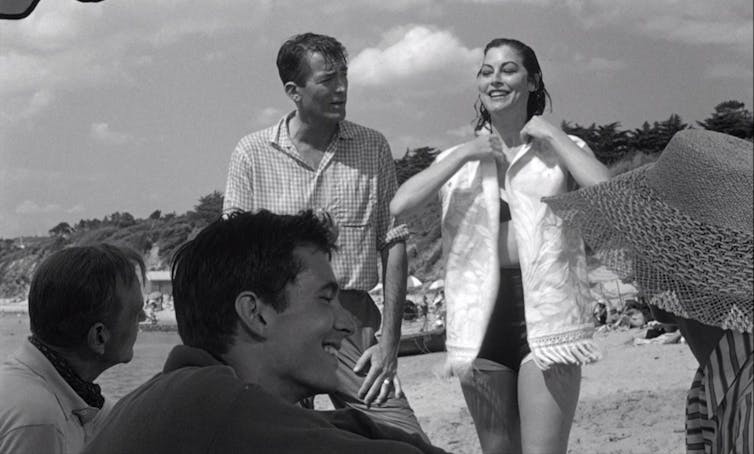

Directed by Stanley Kramer, the cinematic adaptation of On the Beach – which was filmed on location in Victoria and showcased the talents of Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner and Fred Astaire – hit the big screen in December 1959.

Shute famously detested the movie, which received decidedly mixed reviews. In a sense, Shute’s response is surprising, as the novelist clearly wanted to get his message about the perils of nuclear war across to as wide an audience as possible.

Shute’s didactic inclinations are evident towards the end of the novel. “Peter,” the character Mary asks, “why did this all this happen to us?” Even at this late stage, Mary, whose radiation-racked body is spasming uncontrollably, wants to know whether things might have panned out differently. Her husband’s reply is revealing:

‘I don’t know […] Some kinds of silliness you just can’t stop,’ he said. ‘I mean, if a couple of hundred million people all decide that their national honour requires them to drop cobalt bombs upon their neighbour, well, there’s not much that you or I can do about it. The only possible hope would have been to educate them out of their silliness.’

Shute makes a similar point in a letter he wrote in 1960. He holds that a popular writer

“can often play the part of the enfant terrible in raising for the first time subjects which ought to be discussed in public and which no statesman cares to approach. In this way, an entertainer may serve a useful purpose.”

Knowing this, it seems likely Shute would have been delighted to read reviews that praised the book’s “emotional wallop” while simultaneously demanding it “be made mandatory reading for all professional diplomats and politicians”.

While the science in the novel was somewhat flawed, Shute’s cautionary tale undoubtedly spoke to the collective zeitgeist.

Enduring influence

On the Beach was released mere months after the creation of the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy in the United States, and just before the founding of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in the United Kingdom.

Though it seems fair to say Nevil Shute’s general literary standing has diminished in recent years, On the Beach continues to exert a pull on the popular cultural imagination.

The influence of Shute’s novel, which was remade in 2000 as a film for Australian television, can be observed in various post-apocalyptic works, including George Miller’s Mad Max franchise and the late Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. (If anything, the ending of On the Beach is even bleaker than in McCarthy’s masterpiece.)

Shute’s vision of humanity’s self-inflicted destruction is eerily resonant in our time of climate emergency. The nuclear threat remains, too, in our perilous historical moment of democratic backsliding and failing nuclear states.

It seems increasingly likely the world as we know it is coming to an end – if it hasn’t already. The question remains: will it be with a bang or a whimper?

On The Beach runs at the Sydney Theatre Company 24 July to 12 August 2023, with previews 18–21 July. This article was published by The Conversation.