Suddenly people are talking about inflation, even hyperinflation, in a way they haven’t since the 1980s.

In October the United States posted its highest annual consumer price index increase in 30 years, with inflation up 6.2 per cent and “core” (excluding volatile prices) inflation of 4.6 per cent.

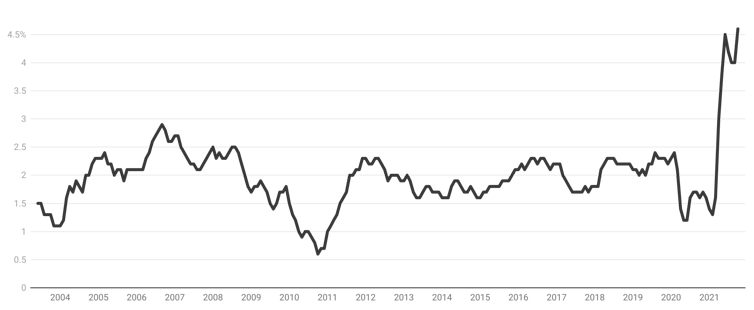

US underlying inflation

US consumer price index for all urban consumers, all items less food and energy, city average. US Bureau of Labor Statistics, St Louis Fed

Former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers – arguably the finest policy economist of his generation – contends that what’s happening is not transitory.

He says soon inflation could soon climb to double digits, where it hasn’t been for 40 years.

There are plenty of other leading economists, including Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman, who argue that what’s happening is just temporary, part of the adjustment to post-pandemic life, akin to the tyres of a car spinning uselessly before they gain traction.

Closer to home, the data are less alarming.

Only 12 of the 55 top economists surveyed by the Economic Society of Australia and The Conversation saw a serious risk of prolonged above-target inflation.

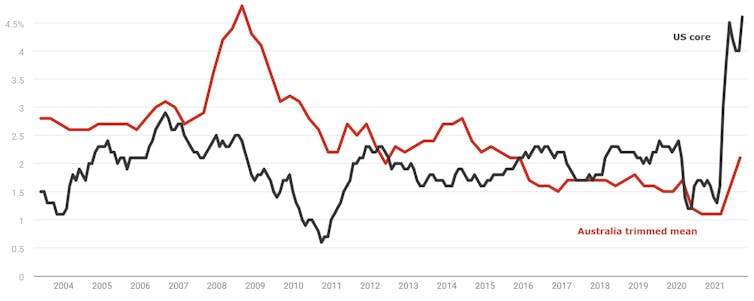

US and Australian underlying inflation

Australian Bureau of Statistics, US Bureau of Labor Statistics

On Tuesday, in an address entitled Recent Trends in Inflation, Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe said in most economies inflation was expected to be lower next year rather than higher, with inflation rates generally clustered around 2 per cent.

That’s RBA-talk for “chill, folks”.

Many wages are barely moving

The Bureau of Statistics reported on Wednesday that the wage-price index climbed 2.2 per cent over the year to September, up from 1.8 per cent over the year to June.

It’s an improvement, but some wages are barely moving. Public sector wages were up just 1.7 per cent and the bureau reported the private sector increase was partly inflated by changes in timing, with fewer September quarter increases than normal last year during lockdowns and a more typical proportion this year.

Four out of ten Australian workers haven’t had an increase for more than a year, compared to 21 per cent at the same time in 2019, before COVID.

Price growth is weaker than it seems

Consumer price inflation appears to be well above wages growth at 3 per cent, but much of this is due to the unwinding of the free childcare available a year ago. Averaged over the past two years, annual headline inflation is just 1.5 per cent.

The official underlying rate of inflation is 2.1 per cent

This doesn’t sound like the Weimar Republic to me.

Is it difficult to renovate a home in Sydney right now? Sure. Is it expensive to buy a car in the US at the moment? Yes it is. But ask yourself why.

Since living through this pandemic, many of us realised we might need and want to spend more time at home and decided to invest in homes better suited to that. And in the US, which is less vaccinated than Australia, many commuters now prefer to drive to work rather than take their life in their hands by catching public transport.

Any debate that sees former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers on one side and current Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen as well as Paul Krugman on the other has got to be legitimate.

But it’s been joined by “inflation “truthers”, conspiracy theorists who claim the US government – in cahoots with corporate interests – have been cooking the books on inflation, something that hasn’t been happening.

While there is always room for debate about the “basket” of goods and services used to calculate the consumer price index, in the US the method hasn’t changed for years.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology Billion Prices Project has trawled through massive quantities of daily data and arrived at much the same conclusions about inflation as the official data.

Australia’s underlying inflation rate has been below the centre of the Reserve Bank’s target band for a record seven years. Too little inflation runs the risk of causing people to delay buying things, sending the economy backwards, which means it has been important to get inflation back up.

Doing it, as we are beginning to, ought to be seen as a policy success.

Yes, we have to be careful not to push inflation too high. But we should also be careful to avoid not finishing the job of getting inflation (and wages growth) back to where they should be. We’ve got some way to go.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.