Ahead of the budget, the government has announced new rules that will allow small businesses at risk of collapse to continue to work out their problems instead of appointing an administrator.

They are needed because of an avalanche of insolvencies awaiting the end of an effective moratorium on bankruptcies (a so-called “regulatory shield”) that expires at the end of December.

Since it was introduced in March the number of companies entering external administration has been unusually low compared to earlier years (at a time of unusually bad conditions) suggesting a buildup of zombie companies waiting to die.

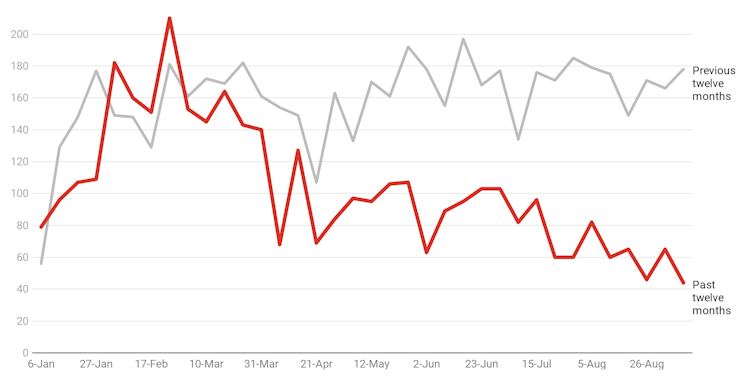

Number of companies entering external administration

Twelve months to each week (red) versus previous twelve months. ASIC

The new rules will allow insolvent small businesses with liabilities of less than A$1 million to keep trading under the eye of a small business restructuring practitioner for 20 days while they develop a restructuring plan to put to creditors rather than surrender control to an external administrator.

If half the creditors by value endorse the plan it will be approved and the business can continue under its present ownership with assistance from the restructuring practitioner. If not, it can be put out of its life quickly under a proposed simplified liquidation process.

Existing laws give directors little leeway

Under the current insolvent trading law, directors are expected to immediately stop the trading when they know or have reasonable grounds to suspect the company is insolvent. Directors who “give it a go” and try to trade their way out of financial difficulty face severe legal consequences: personal liability, a fine of up to $1.11 million per offence or a prison sentence of up to 15 years in extreme cases.

The only way to avoid these penalties is to quickly place the company in the hands of the administrator who temporarily manages the business until the company’s creditors make a decision on the company’s fate.

It’s a regime not particularly suited to small businesses.

The proposed new rules can be seen as a tacit admission of the failure of the “safe harbour” law reform of 2017. Applicable to all companies irrespective of size, it protects directors from personal liability for debts incurred by an insolvent company if they took a course of action “reasonably likely to lead to a better outcome” for the company and its creditors than administration or liquidation.

Anecdotal evidence suggests it is largely shunned by small businesses in part because of its uncapped cost. The fees of small business restructuring practitioners will be capped.

The new laws will create breathing space

The new rules are based on Chapter 11 of the United States Bankruptcy Code, with important differences.

The US law applies to all Companies, not just to those with debts of less than $1 million. And it gives the court an oversight role.

The absence of judicial supervision in what’s proposed for Australia is a double-edged sword. Court involvement generally means delays and high costs.

On the other hand, it provides a valuable check against abuses – such as the deliberate liquidation and rebirth of “phoenix companies” in order to avoid paying debts.

In Australia, that’ll be the role of the small business restructuring practitioner.

It’s not yet clear how they’ll work

It won’t be a panacea for small businesses. They will be required to lodge any outstanding tax returns and pay any employee entitlements before a plan can be put to creditors.

In the current circumstances many small businesses will not be able to comply.

There’s much we don’t yet know about what’s proposed. The government’s briefing says time and cost savings will be achieved through “reduced investigative requirements”. It is unclear to what the extent the liquidator’s wide investigative powers into reasons for business failures will be curtailed.

The changes are likely to have profound implications for many stakeholders, including creditors, employees and the general community.

It is important that the government consults properly before the new rules are put to parliament in time for their introduction on January 1.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.