The city is the densest form of human habitation. The majority of the global population lives in an urban or suburban environment, and in doing so plays an important role in shaping economic, social and cultural production.

The relative proximity to one another provides both benefits and risks – it enables efficient access to resources, services and interactions, but also increases the risk to citizens of exposure to pollution, noise, crime, and contagious diseases.

On 11 March, 2020, the World Health Organisation declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. By the end of March, about 2.6 billion people were under some sort of restricted movement to contain the spread of the virus. This has naturally led to a sharp reduction in transport demand at every level.

The pandemic has cut a swathe through the “normal” life of the city dweller. For most people, the experience of self-isolating and the restricted interaction with others will be entirely novel. Government-prescribed “lockdowns” strike at the heart of our rights and expectations to move about. Public transport is especially hard-hit, with dramatic reductions in ridership.

Public transport is essential because it’s by far the most spatially efficient way to move large numbers of people about the city. However, the notion of sharing confined public spaces for potentially extended periods of time will play heavily on the minds of a public learning to maintain physical distance.

A return to the personal car will create an impossibly large number of trips, with the associated congestion and pollution. For many, public transport is their only option already.

Restoring confidence in public transport

Monash University has strong links with the transport community across a variety of disciplines and expertise. Humans have been spreading and receiving all sorts of pathogens from each other on PT for a long time. Now, patrons are going to be more cognisant that even a “common” cold can be picked up from the casual touching of a button, handle or seat. The idea of physical distancing will prevail long after this pandemic is over.

A Monash multidisciplinary research team encompassing design, social science, medicine, and transportation is opening a dialogue to address how we can translate what we know about public health contagion to develop safer public transport infrastructure that can go some way to restoring confidence in our travel behaviours.

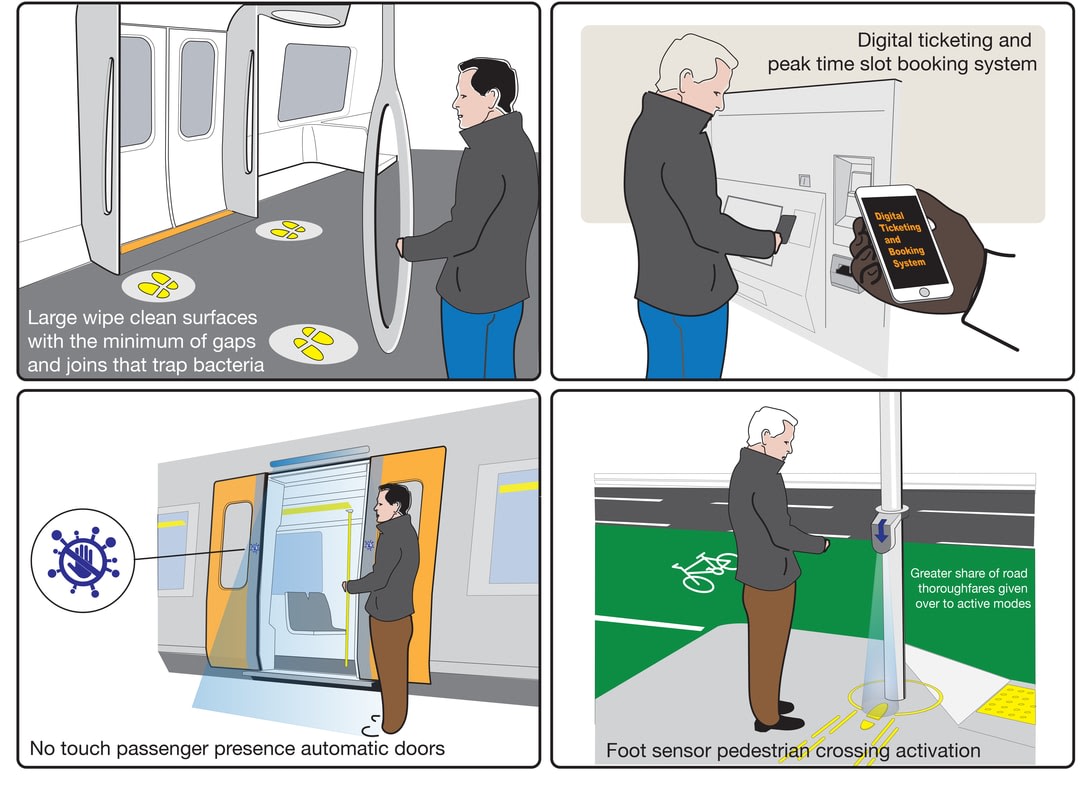

The first thing is to examine our current or pre-COVID-19 travel experiences. What do we touch and pick up to make our journeys? From purchasing tickets, pressing machine keys and screens, placing our hands on barriers, and activating train doors. Steadying ourselves by holding stanchions and strap hangers. All of these unthinking and normal interactions are part of regular experiences on public transport.

We live in fortunate times, in that the technology to reduce these interactions has long been with us. Cashless and digital ticketing is already established in many sectors. Not all customers have, or desire, smartphones, or in cases of disability are able to navigate smartphone technology.

Further investigation into gestural, verbal and non-physical interactions need to be undertaken. Vehicle doors that can sense the presence of a waiting passenger and open automatically are all part of this agenda.

More challenging is the control of vehicle inertia as trains and buses “take off”, creating jerk forces for which standing passengers need to brace themselves, and usually do so by grabbing a stanchion or handrail. Can the materials from which these essential structures are made be improved to be less “sticky” to bacteria or viruses, and can they be cleaned in swift and efficient ways?

Certainly, future interior accommodation will need to address the application of anti-bacterial surfaces, and over larger areas to avoid joints and fittings that could harbour dirt and bacteria. Or is there a market to supply passengers with their own portable strap hangers?

While one might naturally feel a concern for the number of passengers using public transport, there are repercussions for the large number of staff placed in such a public area every day. Their health and safety needs around low-contact measures must also be addressed. This is especially true of those who work in close proximity to transport patrons, such as bus drivers and, of course, taxi services of various types.

Reassessing expectations

In recent years, Melbourne, like other cities, has experienced increased levels of crowding on public transport, with our peak-hour trains regularly exceeding their designed capacity.

There could be limits on vehicle occupancy, either imposed or emerging as a post-COVID-19 population embraces working from home permanently, or adopts behaviour change around active travel such as cycling.

If there’s an upsurge in the migration from both the private car and public transport to take up cycling, then there’ll be increased pressure to re-examine how streets are allocated between modes, and a renewed interest in safety legislation if our “new normal” definition of safety includes being safe from viruses.

During the lockdown, some people have discovered the delights of combining essential trips with exercise, taking their bicycles instead of cars. Might we find that urban space going forward will reflect changes in transport behaviour?

Bringing together science enquiry to inform design strategies will establish a healthy environment to travel in, restore public confidence, and, importantly, continue to encourage migration from private-car use to more sustainable shared and public utilities.

This article was published by Lens. It is part of The Melbourne Experiment, launched recently by Monash University. It’s a landmark interdisciplinary research collaboration to study the effects of the COVID-19 restrictions on the functions of the city. Bringing together senior researchers across the University, The Melbourne Experiment is monitoring key activities and elements of the urban environment before, during, and after the COVID-19.